[co-author: Ken Dai]

The cross-border transfer of personal information (hereinafter referred to as “PI,” and such transfers as “PI export”) is a routine and often essential part of business operations for companies in China—particularly multinational corporations and domestic enterprises that use ERP software provided by foreign vendors with servers located overseas.

With the issuance of the Provisions on Promoting and Regulating Cross-Border Data Flows (hereinafter referred to as the“New Provisions”) in March 2024—which significantly relaxed prior restrictions by raising thresholds and introducing exemption scenarios—China’s regulatory framework for PI export is evolving to strike a balance between national security concerns and the practical needs of international business.

I. Timeline of China’s Regulation on PI Export

China’s regulation to PI export has developed over more than a decade and can be broadly divided into four key phases:

Before June 2017

Before the enactment of the Cybersecurity Law, restrictions on PI export were scattered across industry-specific regulations. A notable example is the 2011 Notice of the People’s Bank of China for Banking Financial Institutions to Enhance Personal Financial Information Protection, which imposed data transfer restrictions in the financial sector.

June 2017 – November 2021

The Cybersecurity Law, which came into effect on June 1, 2017, introduced the first PI export restriction applicable across all industries in China. It required Critical Information Infrastructure Operators (hereinafter referred to as “CIIOs”)—a restrictive group of companies in key sectors proactively identified by Chinese authorities—to submit a security assessment filing with the Cyberspace Administration of China (hereinafter referred to as “CAC”) before transferring PI overseas. However, the scope of this requirement was limited to CIIOs.

November 2021 - March 2024

On November 1, 2021, the Personal Information Protection Law (hereinafter referred to as “PIPL”) came into force, marking a major milestone in China's personal data regulatory regime. The PIPL provides that all PI export activities conducted by entities within China must comply with one of the following three regulatory mechanisms: (1) Security Assessment Notification, (2) Standard Contract (hereinafter referred to as “SCC”) Filing, and (3) PI Protection Certification. In the years that followed, a series of implementing rules were issued to clarify and support the enforcement of these mechanisms in practice.

March 2024 – Present

Prior to March 2024, China had progressively tightened its PI export regime. This trend shifted with the introduction of the New Provisions on March 22, 2024, which marked a turning point in regulatory strategy. The New Provisions relaxed compliance obligations by raising the applicability thresholds for each mechanism and introducing specific exemption scenarios. Since their implementation, the average number of accepted Security Assessment Notifications and SCC Filings has decreased by approximately 60% and 50%, respectively.

Additionally, regulatory requirements have been further eased for PI transfers within the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area, as well as for companies located in pilot Free Trade Zones such as those in Tianjin, Shanghai, and Beijing.

As of today, the key supporting rules for the three mechanisms, which apply uniformly across Mainland China, are summarized below. In practice, Security Assessment Notification and SCC Filing are the most commonly used mechanisms, partly due to their more established procedures.

II. Overview of the Three PI Export Mechanisms Provided by the PIPL

According to the Security Assessment Guideline, PI export refers to the provision of PI that is collected or generated within Mainland China to recipients located outside Mainland China (including Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). In addition to the physical or electronic transfer of PI, actions such as granting access to, retrieving, or downloading such data by overseas recipients also constitute PI export.

The PIPL establishes the following three regulatory mechanisms for entities acting as PI handlers1 in China to lawfully transfer PI overseas.

-

Security Assessment Notification: Submitting a security assessment application to the CAC and obtaining its approval.

-

SCC Filing: Filing the Standard Contract along with the PI Protection Impact Assessment (hereinafter referred to as the “PIPIA”) report with the provincial-level Cyberspace Administration (hereinafter referred to as the “CA”) within 10 working days after signing the contract.

-

PI Protection Certification: Applying for and obtaining a certification of PI protection from the China Cybersecurity Review Certification and Market Regulation Big Data Center, under the State Administration for Market Regulation.

(1) Steps to Determine Applicability and the Corresponding Mechanism

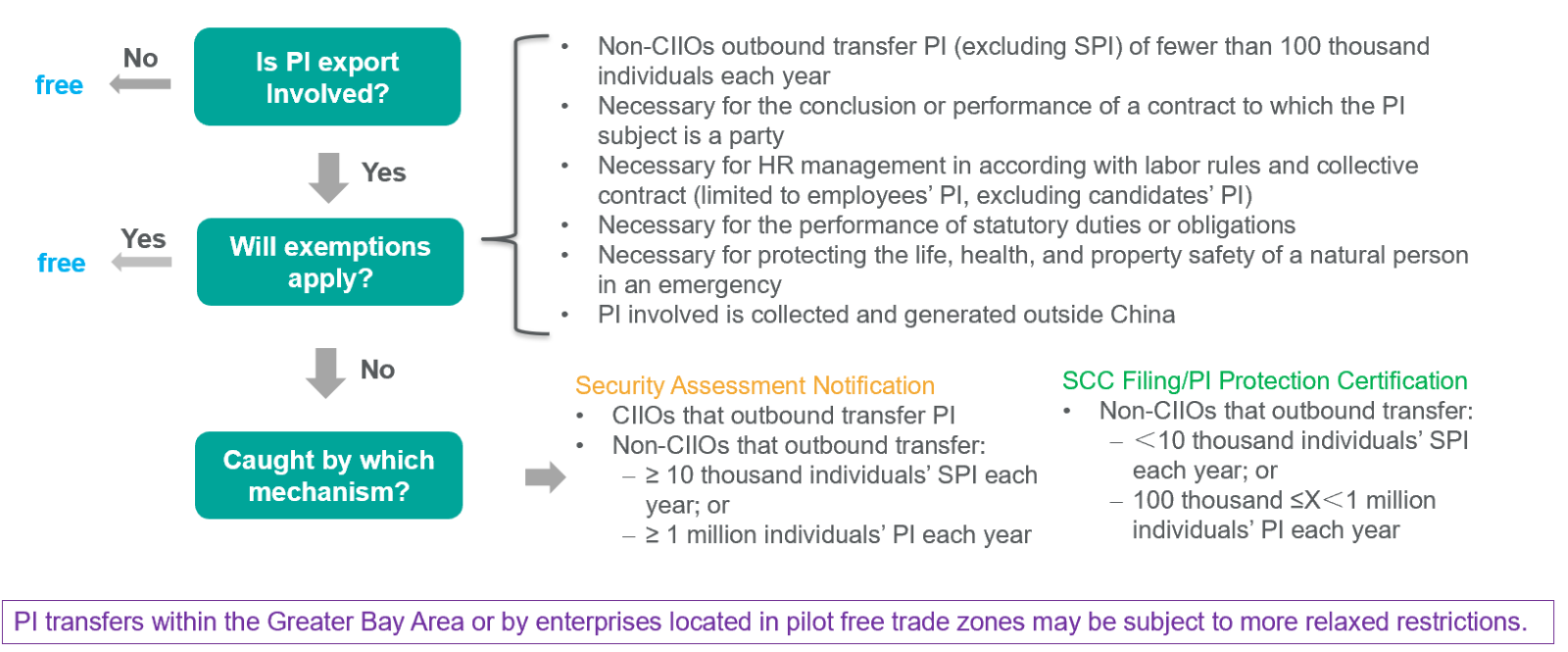

According to the New Provisions, unless an exemption applies, PI (including sensitive PI2, hereinafter referred to as the “SPI”) export activities shall be subject to one of the three regulatory mechanisms. The diagram below outlines the steps to determine whether a specific PI export activity is regulated and, if so, which mechanism applies.

(2) Comparison between Security Assessment Notification and SCC Filing

At present, the legal frameworks for the Security Assessment Notification and SCC Filing mechanisms have been fully established and are widely applied in practice. By the end of 2024, the CAC had completed the review a total of 285 Security Assessment Notifications, with an approval rate exceeding 90%, and had accepted 1,071 SCC Filings.

In contrast, the PI protection certification mechanism remains underdeveloped, with limited practical application. By November 2024, only seven companies, such Alipay and JD, have obtained such certification.

The comparison below focuses only on the two mainstream mechanisms currently in widespread use: the Security Assessment Notification and the SCC Filing.

It should be noted that, regardless of which mechanism is adopted, a PIPIA must be conducted in advance in accordance with the PIPL. The PIPIA should evaluate the following aspects, and the report must be retained for at least three years:

-

Whether the purpose and means of PI handling are lawful, legitimate, and necessary;

-

The potential impact on personal rights and interests, as well as security risks;

-

Whether the protective measures adopted are lawful, effective, and proportionate to the level of risk.

III. Practical Implications

China’s regulation on PI exports is among the strictest globally. With the PIPL in force for over three years, and both the Security Assessment and SCC Filing mechanisms well-established and widely applied, companies engaged in PI export are strongly encouraged to consult qualified local counsel and conduct self-assessments under the PIPL. This helps determine whether their activities are subject to regulation, identify the applicable mechanism, and ensure timely compliance.

Although the PIPL and the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) share a similar overarching structure, they differ significantly in details—particularly with respect to the regulation of cross-border PI transfers. Given that China’s regulatory regime is both newly established and uniquely structured, companies operating in China—especially multinational enterprises—are advised to develop tailored compliance programs that reflect the specific requirements of the PIPL, which will help mitigate the risk of regulatory investigations and potential fines of up to 5% of annual revenue.

Endnotes List

1. Under the PIPL, a PI handler refers to an organization or individual that independently determines the purposes and means of the processing of PI, similar to a data controller under the EU’s GDPR.

2. Under the PIPL, Sensitive PI refers to personal data that, if leaked or illegally used, may easily lead to the infringement of an individual's dignity or harm to their personal or property safety. This includes but is not limited to biometric data, religious beliefs, specific identity details, medical and health information, financial accounts, location tracking data, as well as personal information of minors under the age of fourteen.