Lake Meredith is a reservoir located about 30 miles northeast of Amarillo in the Texas Panhandle. It was formed when the State of Texas built the Sanford Dam on the Canadian River in 1965. When the dam was completed the natural flow of the Canadian River was halted, with only water that naturally filtered through the soil continuing downstream. Damming the Canadian created a rich downstream marshland for cattails, willows, reeds, beavers, and muskrats. It also created fertile ground for the dispute of mineral rights in the newly exposed riverbed.

Although the headwaters of these disputes can be traced back decades, a recent appellate decision in State v. Riemer1 has addressed whether the State of Texas unconstitutionally took valuable oil and gas interests from adjacent landowners along a six-mile stretch of riverbed. Years after the Sanford Dam was completed, these adjacent riparian landowners sued the State for “inverse condemnation” without just compensation. Because the landowners waited so long, the Amarillo Court of Appeals held that their constitutional claims were barred by the ten-year statute of limitations. Before diving into the facts, it helps to start with some basics of streambed mineral ownership in Texas.

I. Ownership of minerals in Texas streambeds generally

In Texas, the ownership of mineral rights in river and streambeds generally depends on whether the waterway is considered “navigable.”2 The test for navigability is not necessarily whether you can don your skipper hat and pilot a 40-foot catamaran down the stream but is more a creature of public utility. As one court has observed, “waters, which in their natural state are useful to the public for a considerable portion of the year are navigable.”3 So, whether you are kayaking the Colorado or tubing the Comal, there is a good chance you are cracking a Coors over State-owned minerals. Conversely, for most non-navigable rivers and streams the minerals are owned by the adjacent landowners up to the center line (or “thread”) of the waterway.

Note that in some instances private owners may acquire by conveyance the minerals under even a navigable waterway. For example, there are historic examples of a land grant from the State purporting to include the beds of navigable streams. The legislature addressed these anomalies by enacting a law known as the “Small Bill”4 in 1929. The Small Bill relinquished certain rights in navigable streams, including the mineral rights, to the adjoining private landowners. However, as illustrated in State v. Riemer, a recorded survey is not a “conveyance” that transfers ownership of a navigable river out of the State.

II. What exactly counts as a streambed?

The boundary line between the bed of a navigable stream and the bordering “riparian” land — being the line between State and private ownership — is not always clear. The Texas Supreme Court has stated that the bed of a stream is “that portion of its soil which is alternately covered and left bare as there may be an increase or diminution in the supply of water, and which is adequate to contain it at its average and mean stage during an entire year, without reference to the extra freshets of the winter or spring or the extreme drouths [sic] of the summer or autumn.”5 If this definition seems as clear to you as Buffalo Bayou6, you are not alone.

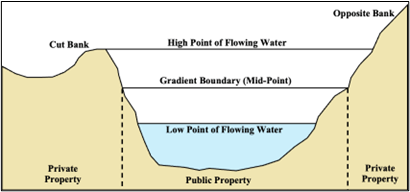

Texas has also adopted what is known as the “gradient boundary” methodology for defining streambeds. The gradient boundary of a navigable stream is ‘‘the water-washed and relatively permanent elevation or acclivity at the outer line of the riverbed that separates the bed from the adjacent upland, whether valley or hill, and serves to confine the water within the bed and to preserve the course of the river.’’7 The boundary between the private riparian landowner and the State of Texas is thus the mean level midway between the line made by the flowing water that just reaches the cut bank (the water-washed and relatively permanent elevation separating the bed from the adjacent upland) and the higher level that just does not overtop the cut bank.8

Complicating the determination of the gradient boundary of a stream is the fact that these boundaries are not static. Streams gradually shift and change course through the processes of accretion and erosion. Accretion is the gradual adding dry land that was previously covered by water. This can be through the deposit of solid material or mud (accretion by alluvion) or by the recession of water (accretion by reliction). Avulsion on the other hand is a sudden change in the bed or course of a stream. These changes may reallocate riverbed ownership rights as between the State of Texas and its bordering riparian owners.

III. State v. Riemer9 background & trial court

In 1937, J.M. Huber Corporation (“Huber”) leased portions of the Canadian riverbed from the state and drilled numerous productive wells. Once the Sanford Dam reduced the navigable Canadian to a trickle, previously submerged lands began to emerge through reliction. According to the landowners, as the water receded the State’s interest contracted to the centerline and the newly exposed lands (and minerals) became private property. Nonetheless, the state continued its relationship with Huber by renewing leases and accepting royalty payments on the 21 oil and gas wells drilled prior to 1982.10

Sometime in the early 1980s, in order to settle the question of ownership, Huber commissioned a resurvey of the disputed portion of the river (the “Shine Survey”). The Shine Survey was filed on January 28, 1982 and identified the gradient boundary of the Canadian by locating the last natural riverbed before the dam’s completion.11 The adjacent landowners later challenged the Shine Survey and identified January 28, 1982 as the key date that the State allegedly began taking their minerals without compensation. However, the landowners did not actually sue on their takings claims until sometime between October 1999 and April 2000 – roughly 18 years later. In 2024, after 40 years in dispute, the trial court awarded the landowners $531,231. These damages were awarded despite the State’s defense that any recovery was time-barred.12 Both sides appealed.

IV. Inverse condemnation & adverse possession

After determining that the landowners had standing to make a constitutional challenge, the court turned to the question of inverse condemnation. Under the U.S. and Texas Constitutions, the government cannot take your property under its eminent domain or condemnation authority without “just compensation.” Similarly, a landowner must be justly compensated if the government takes his land through “inverse condemnation.” Inverse condemnation is a type of government taking that does not involve formal condemnation proceedings. It instead involves taking some other type of action that effectively deprives the owner of the use of his property. Classic examples of inverse condemnation are flooding from a government-constructed dam or zoning laws that severely restrict property use and destroy all economic value.

Texas does not have a specific statute of limitations for inverse condemnation claims. Instead, the Texas courts have analogized the law of adverse possession. They therefore apply the ten-year limitations period set forth in the Texas Adverse Possession Statute (Section 16.026).13 The ten-year clock begins to run when the alleged physical taking occurred — in this case the date the Shine Survey was filed. The ten-year statute also limits adverse possession without a title instrument to a maximum of 160 acres unless the number of acres actually enclosed exceeds 160 acres (in which case there is no acreage limitation).14

Although the Riemer parties agreed that the law of adverse possession applies by analogy in this situation, they disagreed as to which adverse possession rule applies. The landowners first tried to claim that Section 16.026 did not apply because their lands, in the aggregate, exceeded the statutory 160 acres. The court was not sold on this combined-acreage theory. Neither was the court swayed by claims that the 25-year adverse possession statute15 (and not the 10-year statute) should apply. This was because the 25-year statute requires a recorded deed, and the closest thing to a recorded deed the landowners proffered was the Shine Survey. A survey merely describes boundaries and does not transfer ownership. Thus, the court of appeals held that the trial court should have granted summary judgment in favor of the State on its limitations claim under Section 16.026.16

V. Conclusion & takeaway

This case, which cascaded through the court system for decades, ultimately emptied into a sea of non-recovery for the private landowners. Although property owners are constitutionally entitled to just compensation when the government takes their land, they must seek recovery within the ten-year statute of limitations. The Riemer court noted that this constraint exists not to deny justice, but to ensure that claims are brought while evidence remains fresh and witnesses available.17

Per the court: “Like the Canadian River itself, time flows in one direction. The Landowners had ten years to seek compensation for the alleged taking. They waited decades. Neither their understandable desire for compensation nor the complexity of riverbed boundary determinations can extend limitations periods that have already expired.”18 As of the date this article was published, no petition for review has been filed with the Texas Supreme Court.

-

2025 Tex. App. LEXIS 4406 (Amarillo, June 25, 2025).

-

See TEX. NAT. RES. CODE. § 11.041. In 1837, the Republic of Texas modified Mexican civil law by adding the “thirty foot” statute and distinguishing navigable and non-navigable streams. Thus, a stream that has an average width of 30 feet from the mouth up is defined as a navigable stream. TEX. NAT. RES. CODE. § 21.001(3).

-

Welder v. State, 196 S.W. 868, 873 (Tex. Civ. App.—Austin 1917, writ ref’d).

-

TEX. REV. CIV. STAT. ART. 5414a.

-

Motl v. Boyd, 286 S.W. 458, 467 (Tex. 1926).

-

A navigable waterway. Though navigating it is probably not advisable.

-

Oklahoma v. Texas, 260 U.S. 606, 631-32 (1923).

-

Diversion Lake Club v. Heath, 86 S.W.2d 441, 446-47 (Tex. 1935).

-

2025 Tex. App. LEXIS 4406 (Amarillo, June 25, 2025).

-

Id. at 2.

-

This was based on a 1971 Texas Attorney General’s Opinion stating that dam construction does not alter State riverbed ownership. See State v. Sims, 871 S.W.2d 259, 260 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 1994, no writ).

-

2025 Tex. App. LEXIS 4406, at 4.

-

TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE ANN. § 16.026.

-

Id. at § 16.026(b).

-

TEX. CIV. PRAC. & REM. CODE ANN. § 16.028.

-

2025 Tex. App. LEXIS 4406, at 15-17.

-

Id. at 17.

-

Id. at 18.