Judge Bibas’s second take in Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence will get plenty of second looks from courts deciding fair use in generative AI copyright cases.

“Highly fact-specific.” “Narrowly decided.” A case with “potentially limited impact.”

Those were some of the phrases legal commentators used to describe Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith in the days following the Supreme Court’s 2023 landmark fair use decision. Some predicted (or hoped) that Warhol was too tied to its own unique facts to meaningfully reshape how courts would analyze fair use going forward.

But fair use cases are always fact-specific—and that hasn’t stopped Warhol from becoming a fixture in nearly every fair use ruling since, invoked in cases involving everything from architectural plans to Billie Eilish documentaries.

A “Highly Fact-Specific” Case That Will Be Cited Everywhere

Expect a similar trajectory for Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence, Inc. (read here), last week’s summary judgment ruling that handed a win to Westlaw’s owner in the first case to directly address fair use in AI training.

While some have been quick to downplay its significance—pointing to Judge Stephanos Bibas’s explicit disclaimer that “Ross’s AI is not generative AI”—make no mistake: the decision will be cited early and often in the 40+ pending AI copyright lawsuits across the country that do involve generative models trained on massive datasets.

Lawyers on both sides will rely on Ross—some to argue that AI training constitutes infringement even when models don’t output copied material, others to distinguish generative LLMs trained on billions of works from Ross’s narrow, headnote-specific dataset.

Judge Bibas’s About-Face and What It Means for AI Cases

These aren’t easy questions for the judges who’ll decide them, and even Judge Bibas changed his own mind.

His new ruling is a near-total reversal from where he stood less than two years ago, when he denied summary judgment and held that fair use should go to a jury. (He then unexpectedly postponed the trial just four days before it was set to begin, inviting the parties to renew their motions.) Judges ruling on generative AI will face similar challenges.

Many of Judge Bibas’s findings in Ross don’t really hinge on whether Ross’s AI was generative or not. Instead, they focus on whether Westlaw’s headnotes were copyrightable, whether Ross’s training-stage copying involved protectable expression, and whether its use displaced a real or potential market for Thomson Reuters’ original works—some of the same issues that will be decided in cases involving generative AI.

How Original Are Westlaw’s Headnotes, Really?

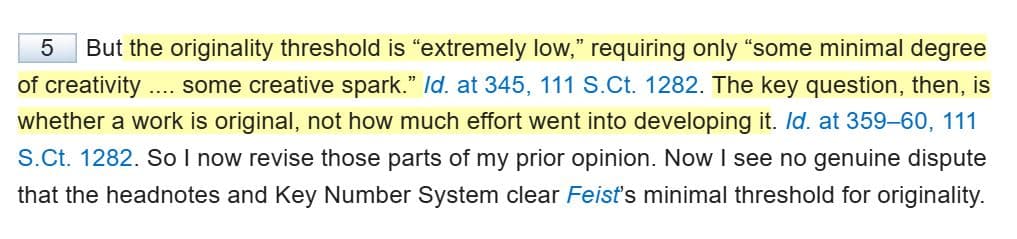

As a threshold issue, Judge Bibas found that Westlaw’s headnotes were original enough for copyright protection. His conclusion that all Westlaw headnotes—including those that quote judicial opinions verbatim—clear the originality threshold is, to put it mildly, expansive.

A copy of something in the public domain can’t support a copyright unless it contains a distinguishable variation that reflects independent creativity. And independent creation simply means you created it yourself, without copying. Yet the court suggested that Westlaw’s mere selection of which words to quote from a judicial opinion renders the headnotes original—an approach that risks allowing monopolization of public domain material.

If you ask me to pick the most important line from “Hamlet,” and I go with “To be or not to be, that is the question,” then rephrase it as “What is: to be or not to be?”—should I be able to copyright that? Can I sue Jeopardy! for turning it into a $200 clue? If so, I’ll see you in court, Ken Jennings.

What About the Merger Doctrine?

It’s important to remember that there are only so many ways to express the key holdings from a judicial opinion, particularly when quoting it verbatim. This is exactly where the merger doctrine—which prevents copyright from restricting ideas or facts when they can only be expressed in a limited number of ways—should have played a more central role. Yet Judge Bibas dismissed that argument in just three sentences. Instead, he likened the editorial judgment involved in selecting which portions of judicial opinions to quote to that of a sculptor choosing what to cut away and what to leave in place.

But that’s a pretty terrible analogy. Sculptors aren’t confined to a limited number of creative choices. It’s more like asking a Westlaw editor to locate Judge Bibas’s key holding on originality in Ross:

…and then expecting the editor to restate it accurately. The result would almost certainly look something like this:

If you got something back like that, congratulations—you have a competent editor. But that doesn’t mean you should have exclusive ownership over the result.

From Headnotes to AI Training

Judge Bibas also found that Ross copied 2,243 Westlaw headnotes in its training memos and that the legal questions in those memos were substantially similar to the headnotes’ protectable elements. How did he arrive at that number? By (his own admission) slogging through them one by one—which, if we’re being honest, seems like exactly the kind of task an AI tool (or at least a sufficiently-caffeinated law clerk) could have handled.

The 2,243 headnotes for which Bibas granted summary judgment were those that, in his view, closely tracked Westlaw’s language but not the language of the underlying judicial opinions. That’s a broad take on protectable expression. Headnotes are only useful if they accurately reflect and quote the key holdings of the cases they summarize—cases that, as government works, aren’t copyrightable.

If the purpose of a headnote is to faithfully distill judicial opinions, then most of what’s in them likely isn’t Thomson Reuters’ protectable expression.

Though questionable, this aspect of Judge Bibas’s holding probably won’t have much bearing on pending generative AI lawsuits, nearly all of which involve claims of verbatim copying of copyrighted works, not summarization.

A post about Westlaw headnotes doesn’t really lend itself to a lot of visuals, so here’s a photo of my cat.

A post about Westlaw headnotes doesn’t really lend itself to a lot of visuals, so here’s a photo of my cat.

One issue that will play a key role in generative AI cases is intermediate copying—reproducing a copyrighted work as an interim step in creating a new work. Courts typically analyze intermediate copying under fair use, where the key question is whether a reproduction serves a transformative purpose or is reasonably necessary to create a non-infringing final work.

Many intermediate copying cases involve computer code, often in the context of reverse engineering—where companies temporarily copy code to develop a new product that does not itself infringe. For example, in Sega Enterprises v. Accolade, the defendant copied Sega’s video games in order to access the functional code necessary to create its own games that would be compatible with Sega’s console. The Ninth Circuit held that Accolade’s interim copying was a fair use because it was a necessary step in acquiring the compatibility code (which was not protected by copyright) and because it increased the public’s access to independently designed video games.

I did a deep dive on intermediate copying several years ago when it arose in a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by Tracy Chapman over a Nicki Minaj demo track that interpolated Chapman’s song “Sorry.” In Chapman v. Minaj, the court ruled that Minaj’s unauthorized recording made fair use of Chapman’s song because it was part of the creative process—used for experimentation and seeking permission, not for commercial exploitation. The court recognized that artists routinely create rough versions of new works before seeking licenses, and that restricting this practice would “limit creativity and stifle innovation in the music industry.” (Chapman denied permission and Minaj’s song was later leaked by a New York DJ, but that’s another story.)

Why the Purpose of Copying Matters

While an intermediate copy can infringe regardless of whether the final output does, the purpose of the copy should factor into the overall fair use analysis. Judge Bibas acknowledged this in his original 2023 summary judgment ruling, stating that whether Ross’s copying was transformative “depends on the precise nature of Ross’s actions.” If Ross’s tool used the headnotes only to learn language patterns for producing quotes from public domain judicial opinions, that would weigh in favor of fair use. If, on the other hand, Ross used the headnotes to train its AI to replicate the creative drafting done by Westlaw’s editors, that would weigh against fair use.

Yet in his new ruling, Judge Bibas ignored this distinction entirely, dismissing Ross’s transformative use argument on the basis that intermediate copying only applies to cases involving functional computer code.

As I discussed in my post on Chapman v. Minaj, courts have in fact recognized intermediate copying in a variety of creative contexts, including literature, music, and film, as well as compilations and databases. Chad Rutkowski has also pointed out that Judge Bibas overlooked WIREdata v. Assessment Technologies, a Seventh Circuit case that found intermediate copying to be fair use in the context of extracting unprotectable facts from a copyrighted database. The comparison is particularly relevant here given that the output of Ross’s AI tool—what Judge Bibas describes as “spitting back” to the user—is an unprotectable judicial opinion, not a Westlaw headnote.

To be sure, the ultimate purpose behind intermediate copying does matter. In Ross, Thomson Reuters had a strong argument that Ross’s copying was not fair use because it was ultimately aimed at developing a direct competitor to Westlaw. But as the court in Sega v. Accolade recognized, it would be overly simplistic to presume that copying to create a competing work is unfair without also considering the purpose and justification for the copying itself.

This should be an additional consideration for courts evaluating large language models, particularly in cases when AI tools at issue don’t generate substantially similar copies of training data, but rather use the material to learn language patterns, styles, or thematic structures.

The Fourth Fair Use Factor and Its Implications for Generative AI

In his 2023 summary judgment opinion, Judge Bibas left the fourth fair use factor (market effect) for the jury, reasoning that “Ross’s use might be transformative, creating a brand-new research platform that serves a different purpose than Westlaw.” He also questioned whether Thomson Reuters would actually use or license its data for AI training.

In his new ruling, he reversed course, finding that Ross intended to create a market substitute for Westlaw and failed to disprove the existence of a potential market for AI training data. Because Ross didn’t show that such a market does not exist or would not be affected, Judge Bibas ruled that the fourth fair use factor tipped in Thomson Reuters’ favor. This portion of the decision is likely to get the most play going forward.

A Facebook ad for Ross Intelligence’s now shuttered legal research tool.

A Facebook ad for Ross Intelligence’s now shuttered legal research tool.

What’s Next?

Courts in pending generative AI cases will face similar fair use questions: Does intermediate-stage copying serve a transformative purpose, and how should that purpose be defined? Do large language models function as market substitutes for the copyrighted works on which they were trained? And how should courts weigh the emerging market for AI training data?

Many news and digital media companies are now licensing their copyrighted works to LLM developers, reinforcing the argument that an AI training data market exists and could be impacted. But unlike Ross, where the AI competed directly with Westlaw, LLMs are trained on billions of works from different sources, creating new outputs rather than replicating the originals. Whether courts view this difference as legally significant remains to be seen, but either way, Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence will be a case that litigants and judges continue to parse as they work their way through generative AI litigation. That’s the benefit—and the burden—of being first.

As courts tackle these novel copyright issues, one thing is clear: AI models aren’t the only ones learning as they go.

View Fullscreen

This post was originally published on Copyright Lately.