[co-authors: Claire Robertson, Eran Sthoeger Esq., Gigi Lockhart, Riley Arthur, Benjamin Crowley]

Key takeaways

- The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of UNCLOS (Implementation Agreement) established a general framework for Deep Sea Mining (DSM) exploration and the protection of the marine environment.

- Since 2014, State Parties have attempted to draft and finalise regulations on DSM exploitation activities. However, a lack of consensus amongst State Parties as to the appropriate balance between exploiting the resources of the seabed and protecting its ecosystems has hindered the adoption of these regulations.

- In 2021, Nauru activated a two-year process to conclude exploitation regulations. Upon expiration of the deadline, contractors would be permitted to apply for exploitation contracts despite the lack of specific regulations.

- While not a legal prerequisite to exploitation, agreement on the exploitation regulations may offer a balance between facilitating DSM exploitation and dispelling the concerns of those States calling for a moratorium, precautionary pause, or ban.

- The International Seabed Authority's (ISA) next session being held this month (in July 2025) will be critical to the finalisation of the regulatory regime to underpin DSM exploitation.

Introduction

While the prospects of Deep Sea Mining (DSM) to provide billions of tonnes of valuable minerals for use in global supply chains has been acknowledged for some time, the development of a legal framework capable of regulating DSM exploitation activities has proven challenging. In Part One of our three-part series, we introduced DSM by shedding light on its drivers, processes, and the science behind it. In this Part Two, we will take a deep dive into the regulatory and legal structure applicable to DSM. While not a legal prerequisite to exploitation, agreement on the Draft Exploitation Regulations may offer a balance between facilitating DSM exploitation and dispelling the concerns of those States calling for a moratorium, precautionary pause, or ban.

Creating the framework for DSM activities: understanding the scope of UNCLOS & the Implementation Agreement

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the 1994 Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of UNCLOS (Implementation Agreement) establish the primary legal framework for DSM activities.

UNCLOS is an international legal framework that governs and regulates activities on and in the ocean, including the abundance of resources which lie beneath its depths. UNCLOS’ scope regulates activities both within and beyond State Parties' national jurisdiction.

UNCLOS permits State Parties to exploit natural resources (living or non-living) within its national maritime zones, such as its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). This means, within a State Party's national jurisdiction, it is permitted to carry out DSM activities for its own benefit, provided those activities comply with UNCLOS’ general protections relating to the marine environment in Part XII.

On the other hand, Part XI of UNCLOS concerns regulation and exploitation of “the Area” – the seabed and subsoil beyond the limits of State Parties' national jurisdiction. Importantly, the Area is considered the “common heritage of mankind” (see Article 136 UNCLOS) meaning the seabed and its mineral resources are not owned by any one State but belong to all of humanity (Article 137 UNCLOS). Activities in the Area must therefore be carried out for the benefit of humankind and in a way that provides equitable sharing of financial and economic benefits (Article 140 UNCLOS).

A key part of equitable sharing of those benefits is the UNCLOS provisions that secure benefits specifically for developing State Parties from DSM activities. Article 148 of UNCLOS makes clear that a key objective of DSM activities is ensuring effective participation of developing State Parties in the Area, “having due regard to their special interests and need … to overcome obstacles arising from their disadvantaged location, including remoteness from the Area and difficulty of access to and from it”. This sentiment is reflected throughout Part XI of UNCLOS. For example, UNCLOS promotes their effective participation through the use of “reserved areas”, seabed sites that only developing countries or the Enterprise (the intended commercial mining arm of the ISA) can access.1 These include certain areas in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), Indian Ocean, and Pacific Ocean. For developing State Parties, the royalty payments and commercial benefits from licensing arrangements with mining companies would provide a significant injection into their GDP. While the royalties are intended to be used for the 'equitable sharing of financial and other economic benefits', the precise royalty sharing arrangements are unknown and currently the subject of negotiations between UNCLOS State Parties.2 Similarly, the transfer of technology and related skills offer substantial benefit to capacity building and upskilling developing State Parties' workforces.

At the time of UNCLOS’ adoption, some States expressed concerns regarding the economic and ideological aspects of Part XI and the DSM provisions, including technology transfer and the role of the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the intergovernmental organisation through which UNCLOS State Parties organise and control activities in the Area. This resulted in several States declining to sign UNCLOS or indicating they could not ratify it unless substantial amendments were made to Part XI.

These objections led to the adoption of the Implementation Agreement in 1994 (Implementation Agreement). The Implementation Agreement substantially amends the DSM regime in Part XI of UNCLOS. These amendments focused on the ISA’s decision-making processes, its funding and how revenue from DSM activities are distributed, and access to DSM technology and transfer. The Annex to the Implementation Agreement details the amendments to Part XI. Importantly, UNCLOS and the Implementation Agreement are to be interpreted and applied together as a single document (Article 2 Implementation Agreement).

The Implementation Agreement codifies the current rules, regulations, and procedures (RRPs) for DSM. The ISA came into existence upon the entry into force of UNCLOS.

Establishing a body to regulate DSM activities: The International Seabed Authority (ISA)

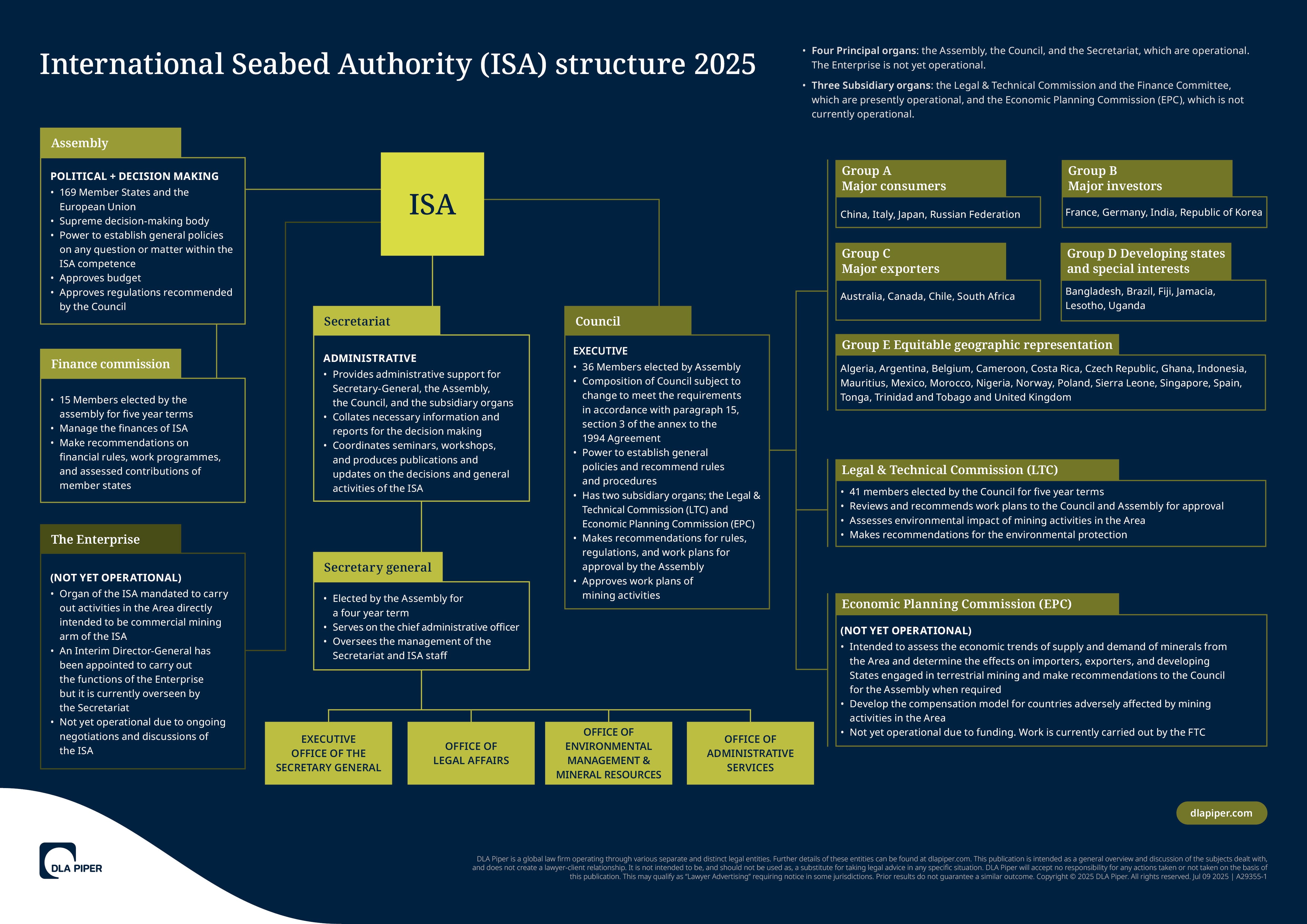

Unpacking the internal structure of the ISA

The ISA is an intergovernmental organisation through which UNCLOS State Parties organise and control activities in the Area, with a view to administering the resources of the Area. Established under UNCLOS and the Implementation Agreement, the ISA “has the mandate to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed-related activities”.3

The seabed and its mineral resources are not owned by any one State, and all rights in the resources in the Area “are vested in mankind as a whole, on whose behalf the Authority shall act”, reinforcing the principle relating to the common heritage of mankind (Article 137(2) UNCLOS). All UNCLOS State Parties are members of the ISA, and the ISA is comprised of several subsidiary bodies:

- The Assembly: The Assembly is comprised of all 170 members with equal voting rights. Appreciating that the rights in the Area's resources vest in the ISA and no individual State Party can exercise authority over the Area or its resources, it is fundamental to have an independent body, representing the interests of all State Parties. The Assembly’s primary roles are developing and agreeing the RRPs, and considering and approving work plans for exploration and exploitation activities in the Area.

- The Council: The Assembly elects a 36-member Council across five categories of interests which forms the Assembly’s executive authority. The Council therefore represents a broad array of interests, comprised of: (a) four State Parties that are significant consumers of minerals to be derived from the Area; (b) four State Parties that are major investors in the Area; (c) four State Parties that are major net exporters of minerals to be derived from the Area; (d) six developing State Parties with special interests, for example land-locked or geographically disadvantaged State Parties; and (e) 18 State Parties to ensure equitable geographic distribution of council members. Ensuring all members are represented in the Assembly, not just coastal State Parties or those with DSM interests, ensures a wide range of views are represented and promotes independence of the ISA in ensuring the principle of protecting the common heritage of mankind is upheld.

- The Legal & Technical Commission (LTC): The Council elects 41-members for the LTC who have “appropriate qualifications such as those relevant to the exploration for, exploitation and processing of mineral resources, oceanography, protection of marine environment, or economic or legal matters relating to ocean mining and related fields of expertise”, taking into account equitable geographic distribution and special interests.4

- The Finance Committee: The Assembly elects a 15-member Financing Committee that plays a central role in administering the ISA’s financial and budgetary arrangements. The members have “qualifications relevant to financial matters and are involved in making recommendations on financial rules, regulations and procedures of the organs of ISA, its programme of work, and the assessed contributions of its Member States”.5

- The Secretariat: The Secretariat serves as the administrative backbone of the ISA, providing comprehensive support to the Secretary-General to fulfill its mandate under UNCLOS and the Implementation Agreement. Leticia Carvalho assumed the role of Secretariat on 1 January 2025, elected by the full ISA Assembly to serve a four-year term. The Secretariat's core functions encompass both operational support and substantive contributions to ISA’s work, producing critical reports, analyses, and policy documents that inform deliberations and decision-making across all ISA organs and subsidiary bodies. The Secretariat plays a vital role in information dissemination through publications, bulletins, and analytical studies, while organising expert meetings, seminars, and workshops that advance ISA’s technical capabilities.

Figure 1: Structure of the International Seabed Authority 2025

Contracting with the ISA

For mining companies and State Parties alike, the ISA holds the key to unlocking DSM. Parties, State enterprises, or natural or juridical persons with the nationality of ISA members (Contractors), are permitted to apply for an exploration work plan. However, to prospect, explore, and exploit minerals, a Contractor must operate in connection with the ISA and a State Party sponsor (the latter of which is responsible for ensuring a mining company complies with UNCLOS).6

As the ISA’s executive organ, the Council, alongside the LTC,7 is responsible for approving work plans for exploration and exploitation. Once the Council approves a work plan for exploration, the work plan is then prepared as a contract between the ISA and the Contractor to undertake mining related activities. For a Contractor to obtain a contract, a State Party to UNCLOS must also sponsor it and satisfy certain technological and financial capacity thresholds.

Currently, the ISA has granted 31, 15-year contracts for mining exploration within an area of approximately 1.3 million square kilometres across the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans. The entities or States which hold those contracts include (but are not limited to) the Governments of India, Poland and the Republic of Korea, Nauru Ocean Resources, Ocean Mineral Singapore Pte. Ltd, Cook Islands Investment Corporation, and Blue Minerals Jamaica Ltd.

The distinction between the exploration and exploitation phases manifests itself in the current work of the ISA. Put simply, exploration is the process of searching for resources, while exploitation is the process of extracting them. As discussed in Part One of this series, these resources include polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides, or cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. To date, the ISA has only granted contracts for exploration activities. No contracts have been issued for the commercial exploitation activities in the Area.

Part of the ISA’s hesitation to issue exploitation contracts stems from the lack of current regulations (or ‘Mining Code’) for DSM exploitation activities.

Developing regulations for DSM exploitation activities

Nauru and the two-year rule

In 2014, the ISA commenced negotiations to draft RRPs for DSM and to develop a “Mining Code”. The “Mining Code” is expected to comprise “rules regulations and procedures issued by the ISA to regulate prospecting, exploration and exploitation of marine minerals in the Area” and represents the overarching regulatory framework for all DSM activities in the Area.8

Frustrated by the delays in the finalisation of the Draft Regulations on Exploitation of Mineral Resources in the Area (Draft Exploitation Regulations), and driven by its desire to commence exploitation, on 25 June 2021, Nauru – a small Pacific Island nation – triggered a key treaty provision (Section 1(15) of the Implementation Agreement). Triggering Section 1(15) started the clock on a two-year countdown within which the ISA was required to finalise the Draft Regulations. Upon expiration of the deadline (regardless of whether the Draft Exploitation Regulations have been agreed), all State Parties to UNCLOS would be permitted to apply for an exploitation contract.

Despite prolonged negotiations over the Draft Exploitation Regulations, the deadline of 9 July 2023 passed with no RRPs on exploitation in place. Delays to the finalisation of the Draft Exploitation Regulations can, in part, be attributed to the scientific unknowns of the potential impacts DSM exploitation technologies may have on the ecosystems of the deep sea, an activity that will likely have a greater impact on the marine environment than exploration. Another contributing factor is the lack of consensus amongst State Parties as to the appropriate balance between exploiting the resources of the seabed and protecting its ecosystems.

Status of the Draft Exploitation Regulations & the ISA’s negotiations

Between 18 and 29 March 2024, the ISA held its 29th Annual Session to continue negotiations as to how to fully regulate DSM. Delegates addressed several key issues that necessarily come into play when formulating effective DSM regulations, including “Environmental externalities. Underwater cultural heritage. Test mining. Equalization measures. Effective control. Regional environmental management plans…”, and the list goes on.9

At the conclusion of the ISA's meetings in March 2024, the Draft Exploitation Regulations were consolidated. The Draft Exploitation Regulations raise several important considerations, including:

- the various approaches to environmental protection in the deep sea, being the precautionary approach, the ecosystem approach, the "polluter pays" principle, intergenerational equity, and an integrated approach;

- the need for environmental impact assessments and statements;

- environmental monitoring and the implementation of an environmental management system;

- a requirement for contractors to take all necessary measures to protect and preserve the marine environment; and

- the ISA’s powers to conduct investigations into non-compliance.10

In Part Two of the 29th Annual Session, held between 15 July and 2 August 2024, the Council continued to consider and negotiate the Draft Exploitation Regulations. While there was acknowledgement that the text was an important milestone and brought the world one step closer to the adoption of permanent regulations, delegates agreed that several outstanding matters would need to be resolved. These matters included the appropriate financial mechanism and benefit-sharing provisions for the receipt of royalties; regulations to guarantee the effective protection and preservation of the marine environment; and institutional arrangements with existing governance.11

The ISA has stressed that DSM exploitation should not go ahead in the absence of any finalised Draft Exploitation Regulations, which will be the key focus of Part II of the ISA's 30th Annual Session being held this month (7 to 18 July 2025).

A “moratorium”, “precautionary pause” or “total ban”: changing tides on DSM exploitation

Despite the Implementation Agreement permitting applications for exploitation contracts, the international community’s understanding of the potential impacts of DSM exploitation have evolved over time, resulting in some States calling for a “moratorium”, “precautionary pause”, or a total ban on DSM.

States calling for a “moratorium”12 seek to halt progress on the development of the Draft Exploitation Regulations and the grant of exploitation contracts until there is further scientific evidence to either confirm or dispel concerns regarding the potential environmental impacts of DSM on the marine environment. Similarly, States calling for a “precautionary pause”13 want to halt exploitation activities until the Draft Exploitation Regulations are completed or such activities can be carried out without compromising the marine environment. On the other hand, a total ban on DSM would prevent any DSM activities and halt the development of the ISA’s regulations to enable a DSM industry.14

In addition to States, several global companies have also voiced concerns in relation to DSM. For instance, France’s Renault15 has indicated that it supports a moratorium on DSM which aligns with the French Government’s position. In March 2021, BMW, Volvo, and Samsung similarly called for a moratorium on DSM until the ecological risks can be better understood.16

The evolving conversation on DSM remained the central theme of Part One of the 30th Annual Session of the ISA, which took place in March 2025. The overarching discussion being that the ISA stands at a crossroads, and that in order “[t]o fulfill its mandate under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to 'organize, control, and regulate activities in the Area,' the Authority will need to balance or resolve competing interests and approaches toward commercial deep-sea mining”.17 Delegates also acknowledged that a tension lies in the fact that while 32 ISA members are calling for a moratorium or precautionary pause on DSM, others want to initiate commercial exploitation of DSM resources as soon as practically possible. While the Council concluded their first reading of the further consolidated text of the Draft Exploitation Regulations, several matters remain outstanding, including effective control, equalisation measures, and provisions relating to inspection, compliance and enforcement. More nuanced issues also arose out of Part I of the meetings, including how to address intangible underwater cultural heritage – matters which speak to the complexities of regulating DSM.18

The hope is that all will be resolved in Part II of the ISA's 30th Annual Session being held this month between 7 to 18 July 2025.

Regulating in the absence of regulations: the ISA’s role pending agreement on the Draft Exploitation Regulations

The interim period between where the two-year time limit has expired and the Draft Exploitation Regulations are yet to be adopted raises interesting and complex considerations regarding the ISA’s capacity to regulate and the role of international law in imposing limitations on States undertaking DSM exploitation activities.

For all DSM activities, the LTC has supervisory responsibilities under Article 165 of UNCLOS. The Council may order inspections of DSM activities under Article 162.

At present, the only activity DSM proponents are engaging in is exploration; no exploitation activities have commenced. Current exploration activities may require less oversight from the ISA due to perceived reduced risk compared to exploitation activities. However, where Contractors can apply for exploitation contracts in the absence of agreed Exploitation Regulations, the ISA may have limited ability to effectively supervise and inspect any DSM exploitation activities.

Absent agreement between the State Parties on the Draft Exploitation Regulations, it is possible for DSM proponents to take advantage of the ISA’s limited enforcement power and conduct exploitation activities in a manner that may not comply with the international community’s expected standards. Indeed, the LTC has reported that several contractors have violated terms of their exploration contracts and the Council is yet to take enforcement or disciplinary action.19 Even if the ISA does wish or intend to exercise its regulatory powers, it presently lacks physical equipment such as submersibles or ocean-going vessels to execute those investigations.20

That said, despite the absence of agreed Exploitation Regulations, States and Contractors are not permitted to operate as they please in the Area. Rather, UNCLOS and the Implementation Agreement must be considered alongside other law of the sea agreements which seek to protect the marine environment. The recently concluded ‘Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity beyond National Jurisdiction’ (BBNJ Treaty), an agreement under UNCLOS’ framework, places clear limits on parties’ activities in the Area. The BBNJ Treaty seeks to protect marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction and facilitate the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s goal of protecting 30 percent of the ocean by 2030 (also known as the ‘30 by 30’ goal).21 Currently 50 countries have ratified the BBNJ Treaty. Consequently, another 10 countries must ratify the BBNJ Treaty before it comes into force.

Part XI of UNCLOS, the Implementation Agreement, and the BBNJ Treaty all operate in areas beyond national jurisdiction. While the BBNJ Treaty does not directly regulate DSM activities in the Area, its environmental impact assessment (EIA) and area-based management tools (ABMT) regimes interact with regulation of the seabed in the Area. Several delegations as part of the ISA meetings have highlighted the importance of considering the BBNJ Treaty when negotiating the Draft Exploitation Regulations.22 For example, the ISA has already developed a regime for EIAs in the Area for exploration activities and is in the process of developing the regime for exploitation activities. The BBNJ Treaty sets a higher bar for EIAs than the ISA currently does which may affect how applications for exploitation contracts in the absence of Exploitation Regulations are assessed. At the same time, the BBNJ Treaty acknowledges that if an EIA for DSM activities in the Area can be considered “equivalent”, the requirement for an EIA under the BBNJ Treaty does not apply (Article 29(4) BBNJ Agreement). Currently, the EIA requirements for exploration activities are considered equivalent as the ISA requires an EIA for any activity that has the potential to cause "harmful effects” and the BBNJ Treaty requires an EIA where “the activity may cause substantial pollution of or significant and harmful changes to the marine environment in areas beyond national jurisdiction”.23 For the BBNJ Treaty, the Party with jurisdiction or control over the planned activity decides whether that activity can proceed following an EIA. However, if a Party determines an EIA is not required, the BBNJ Agreement has a “call in” mechanism that allows other Parties to register their views on the potential impacts of the planned activity with the Party that made the determination and with the Scientific and Technical Body established, but not yet operating, under the BBNJ Treaty.24 The BBNJ Treaty empowers “the BBNJ scientific and technical body to review EIA monitoring reports and to make recommendations to the responsible Party [if it is determined that] the activity could have unforeseen significant adverse impacts or could breach any conditions of approval”.25 However, until the finalisation of the Draft Exploitation Regulations, it is not clear whether the BBNJ Treaty and the ISA standards will be equivalent for exploitation activities.

In any event, the BBNJ Treaty offers protection to the marine environment from potential harm resulting from exploitation activities in areas beyond national jurisdiction. In the absence of agreed Draft Exploitation Regulations, the stringent requirements imposed by the BBNJ Treaty are therefore potentially capable of limiting Contractor’s activities in the Area and regulating DSM activities. This balance between regulation of areas beyond national jurisdiction through the BBNJ Treaty while the ISA completes its regulatory functions, suggestions DSM proponents could proceed in the absence of the Exploitation Regulations.

What might we expect next?

While not a legal prerequisite to exploitation, agreement on the Draft Exploitation Regulations may offer a balance between facilitating DSM exploitation and dispelling the concerns of those States calling for a moratorium, precautionary pause, or ban. As State Parties continue to negotiate the Draft Exploitation Regulations, Contractors may seek to apply for exploration contracts. However, doing so does not mean they are undertaking such activities in a completely unregulated environment. The broad corpus of international law, including the recent BBNJ Agreement, places limits on certain activities in those areas beyond national jurisdiction, offering a potential framework for DSM activities in the absence of the ISA completing its regulatory functions.

In our next article, Part Three, we explore the wider international law issues arising from the calls for a moratorium or precautionary pause, the risks of unregulated exploitation, and the landscape of international and domestic disputes likely to arise in relation to DSM.

1 UNCLOS, art 170, Annex IV; Implementation Agreement, section 2, Annex.

2 Chris Pickets et al, 'From what-if to what-now: Status of the deep-sea mining regulations and underlying drivers for outstanding issues' (2024) 169 Marine Policy.

3 International Seabed Authority, 'About ISA' (webpage, 2025).

4 International Seabed Authority, 'The Legal and Technical Commission' (webpage, 2025).

5 International Seabed Authority, 'The Finance Committee' (webpage, 2025).

6 UNCLOS, arts 139 and 153; Ximena Hinrichs Oyarce, ‘Sponsoring States in the Area: Obligations, Liability and the Role of Developing States’ (2018) 95 Marine Policy 317, 317; see for example, Responsibilities and obligations of States with respect to activities in the Area (Advisory Opinion) [2011] ITLOS Rep 10, [181]-[184].

7 UNCLOS, art 162(2)(b); 165(k).

8 International Seabed Authority, 'The Mining Code' (Webpage, 2025).

9 International Institute for Sustainable Development, 'Summary report, 18 – 29 March 2024' (Online Report, 2024).

10 Draft Regulations on Exploitation of Mineral Resources in the Area (2024), Reg 2, 46, 48, 49, 50 bis, 53 bis, and Part IX.

11 International Institute for Sustainable Development, 'Summary report, 15 July – 2 August 2024' (Online Report, 2024).

12 States calling for a “moratorium” include Canada, New Zealand, Switzerland, Marshall Islands, Mexico, Peru, and United Kingdom, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Palau, and Samoa. See webpage.

13 States calling for a “precautionary pause” include Austria, Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Cyprus Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Honduras, Ireland, Kingdom of Denmark, Latvia, Malta, Monaco, Panama, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Tuvalu, Vanuatu. See webpage.

14 France is the only State calling for an outright ban on DSM. See webpage.

15 Helen Reid, 'Renault and U.S. carmaker Rivian back moratorium on deep-sea mining', Reuters, (Online Article, 11 February 2022).

16 Reuters, 'Google, BMW, AB Volvo, Samsung back environmental call for pause on deep-sea mining', Reuters, (Online Article, 31 March 2021).

17 International Institute for Sustainable Development, 'Summary report, 18 – 19 March 2025' (Online Report, 2025).

18 International Institute for Sustainable Development, 'Summary report, 18 – 19 March 2025' (Online Report, 2025).

19 The Pew Charitable Trusts, 'Seabed Mining Moratorium is Legally Required by U.N. Treaty, Legal Experts Find' (Fact Sheet, July 2023).

20 Daniel Rosenberg, 'The Legal Fight Over Deep-Sea Resources Enters a New and Uncertain Phase', EJIL:Talk! (Blog Post, 22 August 2023).

21 UN Environment Programme, 'Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. 15/4' Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework' (Webpage, December 2022).

22 International Institute for Sustainable Development, 'Highlights and images for 20 March 2023' (Webpage. 20 March 2023).

23 Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction opened for signature 20 September 2023, UN Doc A/CONF.232/2023/4 (not yet in force).

24 Environmental Impact Assessments’ – Factsheet (2024).

25 The Pew Charitable Trusts, 'Inside the New High Seas Treaty' (Issue Brief, August 2024).