On July 10, 2025, in the name of embracing “radical transparency,” the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) announced that it was publishing more than 200 complete response letters (“CRLs”)1 issued in response to drug and biologic marketing applications submitted between 2020 and 2024. The first batch of CRLs that FDA published, however, relates only to previously approved drug and biologic applications, not to pending applications or applications that were withdrawn and not re-submitted. Moreover, nearly all of the letters had already been published in individual product approval packages available through FDA’s drug approval database. Thus, despite the claim that by publishing CRLs FDA would enhance transparency, so far, the agency has only provided a centralized repository of the type of CRLs it has been disclosing for many years.

FDA has suggested, however, that it will go further and start publishing CRLs not only for previously approved products, but also for pending drug and biologic applications. FDA’s July 10, 2025 press release (the “July 10 press release” or “July 10 announcement”) states that the letters that have been published on openFDA are just the “initial batch.” More pointedly, in a July 11 television interview, FDA Commissioner Makary asserted, “Let me be clear . . . it’s going to be real-time,” expressly addressing criticism from media outlets about the scope of the agency’s initial CRL release.2

If FDA were to begin publishing CRLs in “real time” as Commissioner Makary has promised, that would reflect a major change in agency policy. It also would raise significant legal questions. This Client Alert briefly reviews the background on disclosure of CRLs and some of the legal and practical questions raised by the prospect of FDA releasing CRLs in “real time.”

Policy Rationale for “Real Time” Release of CRLs

In its July 10 announcement, FDA claimed that releasing CRLs would deliver greater predictability to drug developers and for capital markets investors, providing “significantly greater insight into the FDA’s decision-making and the most common deficiencies cited that sponsors must address before their application is approved.” The agency further noted that, because it historically had not published CRLs for pending applications, sponsors have been able to “misrepresent the rationale behind FDA’s decision to their stakeholders and the public.”

Questions about the potential disclosure of information from CRLs in not-yet-approved medical product applications are not new. More than 15 years ago, as part of an Obama administration initiative to promote greater openness in government, an FDA task force recommended disclosing the fact that the agency had issued a refuse-to-file or complete response letter in response to an original new drug application (“NDA”), biologics license application (“BLA”), or an efficacy supplement at the time of issuance and, at the same time, disclosing the letters that contained the reasons for the action. The task force noted that there would be significant public benefits associated with disclosing information about not-yet-approved medical products and providing greater insight into FDA’s reasoning behind its actions, including giving the public information on whether and when new medical treatments may become available; providing information on potential off-label uses to health care professionals and patients; and supplying investors with information so that they can allocate limited research dollars efficiently.3 Additionally, the task force found that disclosing refuse-to-file and complete response letters would provide the public with insight into FDA’s application review process. The task force acknowledged that sponsors sometimes publicly disclose the receipt of CRLs and provide explanations for the agency’s decision, but claimed that sponsors may paint an incomplete picture of FDA’s rationale. The task force concluded that the public benefit of more fulsome disclosure could be significant, especially given that “[i]n most cases, those letters will include deficiencies relating to the safety and efficacy of the product.”4

FDA’s July 10 press release announcing the publication of more than 200 CRLs echoes goals articulated by FDA in the past: increasing transparency and combating misinformation spread by sponsors. The press release highlights agency concerns that when companies receive a CRL, they have an opportunity to hide, minimize, and misconstrue FDA’s reasons for rejecting their applications. The announcement cites a 2015 FDA analysis that purportedly identified discrepancies between 61 CRLs issued by FDA from August 2008 until June 2013 and the press releases that companies issued regarding the CRLs.5 No press release was issued for almost one-fifth of the CRLs, and the press releases that were issued following a CRL often failed to discuss FDA concerns related to safety and efficacy, including in situations where there were higher mortality rates in treated patients.

In a July 11 Washington Post op-ed, Commissioner Makary explained how making CRLs publicly available could also help to shrink the drug development timeline.6 He said that during recent closed-door CEO listening tour sessions, attendees expressed frustration with not having a clear understanding of reviewers’ requirements, which they said results in unnecessary work. Dr. Makary said he hopes that giving manufacturers a real-time view into FDA’s concerns about other applications will translate into reduced research and development costs, which may ultimately serve the current administration’s priority of reducing drug prices.

Potential Legal Obstacles to “Real Time” Disclosure

While some advocates have pushed for CRL disclosure for years, FDA has never disclosed CRLs related to not-yet-approved products. The agency’s delay may have resulted from concerns regarding the legal risks of disclosure.

Indeed, in another interview, Commissioner Makary stated that the agency’s new CRL policy was established following a “long set of meetings with our lawyers to determine that we can do this.”7 How did FDA’s lawyers become comfortable with those risks? And where do they intend to draw important lines with respect to which CRLs to release, when to release them, and what processes to follow in doing so? We will likely gain insight into these questions only if and when FDA makes good on its promise to release CRLs at the time of issuance, or if it ultimately has to defend its position in litigation.

FDA Regulations. FDA’s regulations currently prevent the agency from disclosing even the existence of pending NDAs or BLAs unless the existence of the applications has been publicly disclosed or acknowledged.8 If the existence of an unapproved application has not yet been publicly disclosed or acknowledged, FDA is prohibited from disclosing data and information in the application.9 Even if the existence of an application has been acknowledged, FDA must redact trade secrets, confidential information, and individually identifiable patient information from any materials disclosed. The 2010 task force noted that FDA’s practice is to treat a “substantial amount” of information submitted to FDA that does not qualify as protected trade secrets as “confidential commercial information that is not publicly disclosed.”10 The task force recognized that changes to regulation and possibly even legislation might be required to implement proposals to make CRLs and other similar information public.11 Commissioner Makary has acknowledged that “private commercial information belongs to the applicant” but has argued that “the deliberations of agency scientists are not the property of the drug’s sponsor.”12

There is also an exception in the drug regulations to the general prohibition against disclosure of information related to a not-yet-approved medical product. If the existence of an NDA or BLA has been publicly disclosed or acknowledged, the FDA Commissioner may release a “summary of selected portions of the safety and effectiveness data” if appropriate for “public consideration of a specific pending issue.”13 This exception is relied upon, for example, when a medical product is considered during an FDA advisory committee meeting.14 In theory, this exception might provide a pathway forward if FDA discloses the CRLs where the existence of the underlying application has been acknowledged on the basis that consideration of the safety and efficacy of a specific medical product application is a “pending issue.” Nonetheless, whether the generalized policy considerations that FDA has asserted as favoring CRL disclosure are sufficient to constitute a “specific pending issue” subject to “public consideration” is far from clear. Likewise, there would be a serious question as to whether releasing the text of a CRL could constitute a “summary of selected portions of the safety and effectiveness data” in an application.

Other Potential Obstacles to Disclosure. One way FDA might seek to address the limitations imposed by the disclosure regulations would be to revise them to provide the agency with more latitude. Some have suggested, however, that other federal statutes would prohibit FDA from doing so. In particular, the Federal Trade Secrets Act imposes criminal liability on a government official who discloses any information submitted to the government that “concerns or relates to the trade secrets, processes, operations, style of work, or apparatus, or to the identity [or] confidential statistical data . . . of any person, firm, partnership, corporation, or association . . . .”15 This definition of trade secret encompasses at least some information that may be considered “confidential commercial information” under FDA regulations. In addition, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act also prohibits the public disclosure of information acquired under numerous provisions of the statute “concerning any method or process which as a trade secret is entitled to protection.”16 Violation of this prohibition is also criminally chargeable.

To date, no changes to FDA disclosure regulations have been made, leaving open the possibility that steps to embrace “radical transparency” by publishing CRLs for pending applications may invite legal challenges. FDA could seek to revise its regulations to allow greater flexibility in releasing CRLs, but its authority to do so may also be limited by the federal statutes discussed above. Alternatively, FDA could seek statutory changes from Congress, but doing so would, of course, present its own challenges.

Potential Practical Challenges with Real Time Disclosure

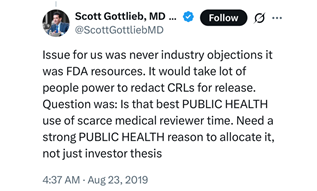

Even assuming the legal questions were overcome, FDA would face a practical challenge with real time disclosure of CRLs. In 2019, the question of CRL disclosure arose again under the first Trump administration. Former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb pushed back on the notion that industry was preventing FDA from releasing all CRLs, writing on Twitter that limited FDA resources is the reason for not disclosing CRLs.17

FDA’s July 10 announcement does not discuss the question of agency resources. Public reports suggest that FDA’s FOIA resources have been stretched thin amid ongoing reorganization and reductions in staff.18 Although FDA has reportedly rehired some FOIA staff, it remains unclear how current staff capacity compares to before the firings.19

Unanswered Questions

FDA has not specified which types of CRLs will be subject to the new disclosure policy. The 2010 task force draft proposals carved out CRLs issued in response to abbreviated new drug applications, abbreviated new animal drug applications, chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (“CMC”) supplements, and labeling supplements from the proposal to make CRLs public before applications are approved.20 The task force acknowledged that disclosing CRLs related to these types of applications would be of little use to the public and would not serve public health interests because they do not relate to safety and efficacy issues. In particular, CMC supplements contain a large volume of trade secret information. Disclosing the supplements would require such heavy redaction that they would provide very little actual information to the public. The task force found that CRLs issued in response to labeling supplements are also unlikely to be useful to the public, as they contain details of drug-specific labeling negotiations and provide little insight about the rationale underlying FDA’s drug review process. The task force found that the public health interests in such letters would not warrant the “significant resources entailed in proactive disclosure.”21 Only as FDA begins publishing more CRLs will it become clear which types of CRLs it plans to publish going forward.

It also remains to be seen whether FDA’s plan to publish CRLs in “real time” means that CRLs will be published roughly contemporaneously with their issuance or whether there will be a window between issuance to a sponsor and publication. Presumably, there will have to be some time lag to allow for redaction of trade secret and confidential commercial information. If there is time between issuance and publication of the CRL, FDA has not indicated whether companies will be provided an opportunity to review and comment on redactions prior to publication.

Additionally, FDA’s policy announcement only addresses human drug and biological products. The 2010 task force raised similar questions about other FDA-regulated product types, including animal drugs and medical devices. To date, FDA has not addressed whether it will seek to release similar information for such product applications. Manufacturers of such products should closely monitor FDA’s actions relating to CRL disclosure for drug and biological products as well as FDA statements relating to the scope of its “radical transparency” initiative.

Conclusion

FDA’s announcement that it will publish CRLs for NDAs and BLAs, and Commissioner Makary’s subsequent comments that the agency will do so “in real time,” have made waves in the media as reflecting a new FDA “radical transparency” agenda. To date, the agency has yet to disclose any information that has not been previously published and would justify the press hype. If FDA were to proceed with disclosing CRLs in real time, we expect to see significant legal, practical, and policy questions raised about the agency’s actions.