In October 2023, we reported on the district court decision in Sonos, Inc. v. Google LLC.[1] The decision was notable for reviving the prosecution laches doctrine to render unenforceable a continuation patent filed 13 years after the original application.

Last week, the Federal Circuit reversed. Google LLC v. Sonos, Inc., 24-1097, 2025 WL 2473258 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2025). Although it reversed, the Federal Circuit left the door open for prosecution latches in similar cases.

Prosecution Laches Was for Pre-1995 “Submarine” Applications

Prosecution laches is an equitable doctrine that has rendered unenforceable so-called submarine patents that issued from applications filed before 1995. Before 1995, U.S. patents lasted 17 years from issuance. Applicants could keep applications pending (sometimes secretly) for years or decades while they watched how an industry developed, then later add claims to cover industry trends. The later-issued claims still enjoyed an early priority date and a full 17-year enforcement term. But if others were prejudiced by the applicant’s “unreasonable and inexcusable” prosecution delay, courts could hold the later-issued claims unenforceable under the prosecution laches doctrine.[2]

Submarining changed in 1995, when patent terms began running from the date of application. Applicants still can (and often do) file continuations long after their original applications, which allows them write claims to cover industry trends while still enjoying an early priority date. But now, waiting shortens the patent term.

The Federal Circuit has never endorsed prosecution latches for post-1995 applications.

The District Court Extended Prosecution Laches to Post-1995 Continuation Applications

In Sonos, District Judge William Alsup applied prosecution laches to post-1995 patents. The decision drew widespread attention for its potential implications on the common practice of filing serial continuations.

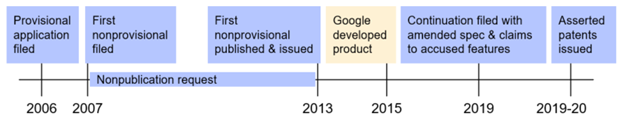

The case involves Sonos patents that issued in 2019 and 2020 but claim priority to 2006. Sonos’s prosecution strategy made it harder in several ways for competitors to know what it would later claim:

- Sonos waited 13 years between filing its provisional application and filing for the patents it asserted.

- Sonos requested nonpublication for its first nonprovisional application, thus keeping its specification and provisional application from the public for seven years, until 2013.

- Sonos amended its specification to add material that had been incorporated by reference from an appendix to its provisional application.

- Sonos may have purposely drafted its later claims to capture industry trends.

Judge Alsup deemed Sonos’s 13-year delay unreasonable and inexcusable. He reasoned that it “would have been a small step for Sonos” to pursue the asserted claims earlier.[3]

And Judge Alsup found prejudice to the accused infringer, Google, which began investing in the accused products by 2015. Sonos argued that Google could have simply reviewed Sonos’s prosecution history before making those investments. Judge Alsup rejected that argument. Because of (1) Sonos’s nonpublication request, (2) the addition of matter from the provisional application, and (3) the lack of earlier claims directed to the features in the asserted claims, Google could not simply have avoided prejudice by reviewing Sonos’s applications.

The Federal Circuit Reversed, But Left the Door Open for Prosecution Laches

The Federal Circuit reversed on somewhat limited grounds, in a non-precedential decision authored by Judge Lourie.

The Federal Circuit did not say whether a continuation filed 13 years after the original application could be considered unreasonably and inexcusably delayed. Instead, the court “limit[ed] [its] discussion” to Google’s showing of prejudice.[4] The Federal Circuit offered two independent reasons the district court got that part wrong:

First, Google offered no evidence that it began investing in its products by 2015 or that it was unaware Sonos had already invented the accused functionality at that time.

Second, Sonos’s first application published in 2013—before Google’s investments. The court ruled that the 2013 publication disclosed the later-claimed invention (even without the material incorporated by reference and later inserted into the specification). The court held that Google “cannot be prejudiced by incorporating into its products a feature that was publicly disclosed in a patent application prior to its investment.”[5]

Although the Federal Circuit has eschewed precise requirements for prosecution laches,[6] these two reasons suggest two potential bars to prosecution laches: actual knowledge of the invention, and a published specification with written description support for the later claims.

But by issuing a non-precedential decision and addressing only parts of Judge Alsup’s reasoning, the Federal Circuit leaves itself and the lower courts flexibility to apply prosecution laches in similar circumstances. The case could have come out differently—if, for example, the accused infringer proved it invested in developing a product while the patentee’s specification was unavailable under a nonpublication request; or if essential written description support had been only incorporated by reference into the published application. In either scenario, the Federal Circuit’s opinion would not necessarily bar prosecution laches.

Judge Alsup’s opinion may therefore live on as a guide for accused infringers to prove prosecution laches.

Practical Implications

Applicants should be careful with nonpublication requests. A nonpublication request can help an accused infringer prove the prejudice element of prosecution laches. Specifically, nonpublication could prejudice the accused infringer if it prevents their reviewing the specification as they began investing in the accused product. Sonos’s patent was saved by the fact that Sonos’s application first published before Google said it began investing. But the outcome could have been different if the nonpublication had gone on longer or Google had started work sooner.

Freedom-to-operate assessments should consider the specification and future claims. This decision reaffirms that a comprehensive FTO analysis includes hypothetical claims that could be granted in future continuations for live U.S. patent families. Under the reasoning of Google v. Sonos, prosecution latches will not likely be an available defense for any inventions disclosed in a published specification but only later claimed.

[1] Sonos Inc. v. Google LLC, 20-06754 WHA, 2023 WL 6542320 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 6, 2023).

[2] Cancer Rsch. Tech. Ltd. v. Barr Lab’ys, Inc., 625 F.3d 724, 729 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

[3] Sonos, 2023 WL 6542320, at *17.

[4] Slip Op. 15.

[5] Slip. Op. 16.

[6] See Symbol Techs., Inc. v. Lemelson Med., Educ. & Rsch. Found., 422 F.3d 1378, 1385 (Fed. Cir.), amended on reh’g in part, 429 F.3d 1051 (Fed. Cir. 2005).