Introduction

Often, forensic accountants face practical challenges when calculating business interruption (BI) losses. These issues have been highlighted by recent claims following COVID-19 and the 2024 storm in the UAE which caused widespread flooding and high volumes of claims.

BI policies may include Gross Profit wording, such as:

“Gross Profit: The amount by which: (a) The sum of the Turnover and the amount of the Closing Stock and Work in Progress shall exceed. (b) The sum of the amount of the Opening Stock and Work in Progress and the amount of the Uninsured Working Expenses as set out in the Schedule. NOTE: The amounts of the Opening and Closing Stocks and Work in Progress shall be arrived at in accordance with the Insured’s normal accountancy methods, due provision being made for depreciation.”

Other similar wordings (or variations thereof) are available, but the preceding paragraph is close to typical wording seen in the UAE (drawing upon UK wordings).

Forensic accountants, when discussing policy wording, caveat our analysis to make it clear that we do not interpret or opine on this topic and would always defer to underwriters (and professionals in the legal realm) to resolve any discrepancies arising. Notwithstanding this, time and time again, we come up against practical challenges when calculating business interruption (BI) losses.

Some of these issues have been highlighted in the past in Riley on Business Interruption Insurance [1] and/or the paper compiled by CILA/CII on “Challenges highlighted by claims experience,” [2] and this is not just a UK problem.

With COVID-19 there were many complexities related to “non-damage” and “disease” extensions (beyond the scope and focus of this article), but with the 2024 storm (and resultant flooding) these claims were relatively straightforward property damage.

On the property damage side, the loss adjusters were challenged by the sheer volume of claims, whereas for forensic accountants, the low levels of penetration in respect to business interruption coverage resulted in a lower frequency of claims.

Many people and businesses that were affected had never made claims before. Many had probably never even read the policy wording.

This highlighted differences in terminology, misunderstanding of the policy wording, gaps in coverage, and a general lack of understanding.

How Opening Stock, Closing Stock, and WIP Affect Business Interruption Insurance Claims

One point of confusion for non-accountants is the reference to closing stock, work in progress (WIP), and opening stock in the gross profit definition.

Often a layman (or even a non-financial member of the C-suite) is more familiar with cost of goods sold (COGS) or cost of sales (COS) when discussing gross profit (or gross margin); therefore, in the absence of a forensic accountant to explain the commonalities and nuances there can be some talking “cross purposes” between insurers, adjusters, brokers, and the insured (sometimes a combination of insurance team, legal, operations, and accounting staff).

Opening stock refers to the inventory balance at the start of an accounting period, representing goods on hand and ready for sale or use. This usually comprises raw materials (those which go into a production process) finished goods (products which are ready for sale), and WIP (items that have started production but are not yet finished).

Stock (or inventory) figures appear in the balance sheet (also known as the statement of financial position (SOFP) as a current asset of the business, whereas gross profit appears in the profit and loss statement (P&L) (also known as the income statement or statement of comprehensive income [SOCI]).

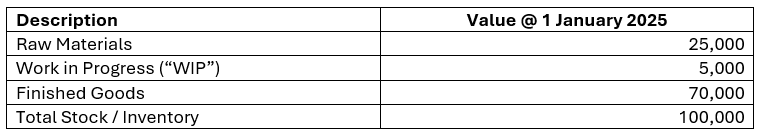

Take, for example, ABC LLC’s opening balance [3] on 1 January 2025:

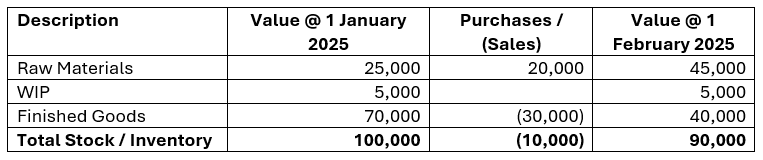

Let us assume, during the month, ABC LLC purchased 20,000 of raw materials and finished goods reduced by 30,000 due to sales. The overall stock balance would be reduced by 10,000 as illustrated below:

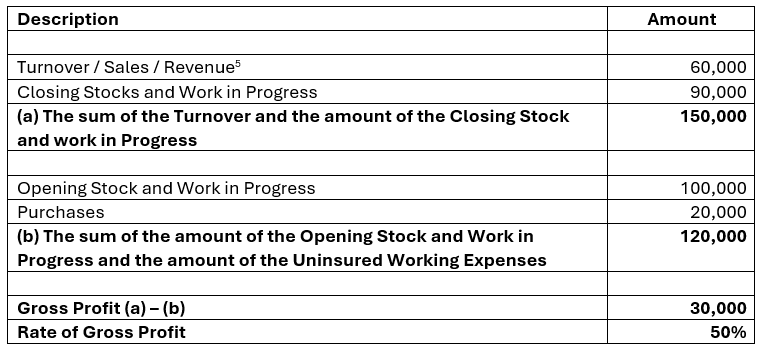

From an insurance policy calculation perspective (let us assume for simplicity that only purchases of raw materials are uninsured working expenses [4]) the computation would be as follows:

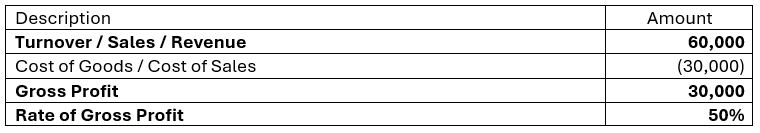

In reality, the insured’s P&L / management accounts may simply express a COGS/COS figure as follows:

From a practical perspective, in this case, the COGS / COS can be used directly to compute the gross profit, effectively shortcutting the calculation of the change in stock position. However, care should be taken to understand how COGS / COS is computed to ensure consistency with the policy language, particularly where the insured’s accounting definition of gross profit varies from that which is included in the policy schedule.

Typically, where an insured has a sophisticated accounting or enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, the calculation of COGS / COS is done “automatically,” taking into account not only the change in inventory [6] but all manner of complex accounting principles such as absorption costing (the allocation of certain fixed or semi-fixed expenses against a product’s cost) or standard cost variances (e.g., changes in purchase price of raw materials). This becomes even more complex when the insured sells multiple different product types or SKUs which can skew the gross profit depending on the sales mix. The departmental clause can be useful to more accurately determine the gross profit of the product or department affected by the incident. [7]

In the absence of a forensic accountant, these issues could be overlooked or ignored.

Conversely, where the insured has a less sophisticated accounting system, it may be that we must rely on the annual financial statements along with a combination of system extracts and/or spreadsheets—which are maintained—in order to calculate.

We have also seen examples where, in pursuit of “following the policy wording,” the calculations presented have comingled balance sheet and P&L items from different time periods (e.g., some from the indemnity period, some from the prior year, and others from the year end audited financial statements) and have been completely wrong, conceptually.

In some cases, the “trends” or “special circumstances” clauses have been poorly understood or applied (or, in other cases, not applied) in relation to both turnover and gross profit.

For those businesses which were partially open, it may not be appropriate to apply the post-loss rate of gross profit due to a change in product mix (e.g., where only certain product lines were able to be sold due to the absence of a machine or line, or damage to particular batches of stock in the flood).

For other businesses, there may have been annual price changes taking place which may have impacted sales prices and/or input costs which may render the results in the 12 months prior to the incident irrelevant to the experience which would have taken place during the indemnity period.

However, for the most part, the main discussions surrounded what was intended to be deducted as an uninsured working expense.

Challenges in Defining Uninsured Working Expenses in Business Interruption Insurance Policies

We found that many policies simply contained the “default” or “pre-printed” uninsured working expenses [8] of:

- Purchases.

- Carriage, packing, and freight.

- Wages.

- Bad debts.

Sometimes it can be questioned whether anyone has thought about the definition (e.g., how does “carriage, packing, and freight” apply in the case of a hotel business? Does this extend to transfers, excursions, and hotel cars?).

Even more concerning, you may find the words “appropriate list to be inserted” when turning to a schedule or definitions page.

At the time of policy placement, the insured should have the option to deduct further costs (in addition to the four mentioned in the paragraph above) if they consider these will vary directly in line with turnover. However, care must be taken with costs which continue during a partial loss/outage which the insured may have assumed would cease in a total loss scenario.

Even in a total loss scenario, we have seen examples where the insured has been subject to take-or-pay agreements or has an obligation to receive certain supplies (e.g., waste recycler) or has even been required to continue 100% of purchases during a partial interruption and, as a result, has had to operate inefficiently (e.g., they can only make one product due to the absence of a machine/line). Therefore, even raw material purchases are not always certain to cease or reduce proportionately depending on the business model or loss circumstances.

In cases where the definition was missing or incomplete (or the sum insured for gross profit was completely different—both higher and lower—between the policy and the financial statements), further investigation was undertaken to confirm what documentation had been provided to the insurer and/or broker at policy placement to try and understand the intention. Some had clear workings and spreadsheets in submissions which could be traced back to both the sum insured and the insured’s financial records. Others, we could only deduce that sum insured figures date back years, having been “rolled over” for multiple years of renewal with no change.

Areas for Clarity in Business Interruption Policy Terms: Purchases and Wages

In some instances, there were misunderstandings as to what is meant by certain policy terms, particularly “purchases” or “wages.”

Defining “Purchases” in Business Interruption Insurance

One theory advanced by an insured held that purchases should mean those that count towards vatable inputs that can effectively be offset against a vatable sale/supply under UAE VAT rules. [9]

However, purchases are generally understood by insurers to be the purchase of raw materials, but the insured had also presumed this would also extend to purchases such as outside services, subcontracting, utilities, etc.

In the extreme, the insured may also believe this includes purchases of capital machinery.

Depending on the circumstances, the ambiguity could cause an argument for a wider or narrower scope of the definition where the intent is unclear—particularly, where this could impact the sum insured adequacy.

Perhaps a tightening of the wording (e.g., “purchases of raw materials or goods for re-sale”) and/or provision of a more detailed sum insured calculation breakdown / scenario at the placing / underwriting stage would help to address this issue.

Clarifying “Wages” Versus Salaries

In respect to “wages,” this term is sometimes used interchangeably with salaries, although some schools of thought suggest salaries typically refer to a fixed amount per pay period (per month / per week / biweekly), while “wages” refer to amounts paid per hour which typically have more variability.

Adding to the possible confusion in terminology, in the UAE, salaries for most private sector employees are paid through the wages protection system (WPS), an electronic salary transfer system managed by the Central Bank of the UAE, with the aim of ensuring secure and timely payment to employees.

In reality, most (if not all) staff in the UAE are salaried, and most payments will not cease or reduce in the event of a loss. [10]

Since more than 85% of the UAE population is made up of expatriates, there is also a significant cost associated with hiring and paying for flights; therefore, in the event of a short or partial closure, it is unlikely that employees will be let go. However, at the lower end of the spectrum there is a high churn rate amongst unskilled workers, and, therefore, in longer outages it is possible there may be lower-paid workers leave, which may not be immediately replaced. However, with visa restrictions across the GCC (particularly Saudi Arabia) we have seen companies immediately replace staff even when closed in order to retain visa quota.

Many businesses show employee costs below gross margin or contribution in their management accounts, indicating the “fixed” nature of labor costs.

Elsewhere in the world there is sometimes the distinction between ordinary payroll (wages and/or salary of the normal workforce, e.g., production staff) and key personnel (usually senior salaried positions) but this terminology is not commonplace here.

Again, perhaps a tightening of the wording (e.g., “wages of hourly-paid staff”) would assist in addressing this issue.

“Shall Be Arrived at in Accordance with the Insured’s Normal Accountancy Methods”

The problem with the wording, “normal accountancy methods,” is that there is no universal definition of gross profit, and the insured’s normal accountancy method may even directly conflict with the definition included in the insurance policy wording or may vary between the insured’s management accounts and the audited financial statements.

Gross profit in the audited financial statements will generally have more costs deducted than defined in the insurance policy, which is one of the reasons why policyholders can find themselves underinsured. [11]

Adding to the possible confusion, sometimes there will be a note such as, “the words and expression used in this definition shall have the meaning usually attached to them in the books and accounts of the insured.” Upon inspection, there is no ledger account which uses the same terminology as the policy wording.

Arguments from the insured often revolve around its understanding of gross profit in the context of its management accounts, which is often more closely aligned with “contribution” or “margin” (i.e., sales less variable costs).

Alternatively, there is sometimes an argument advanced that the insured’s understanding at the time of policy placement was more aligned with the definition of gross profit in its audited financial statements (often the case where there is significant underinsurance) and it had not appreciated the difference between this and the policy definitions. In some cases, the insured was able to demonstrate the sum insured figure had been directly lifted from its latest audited financial statements.

Where there are grey areas, this can lead to contra proferentem arguments from the policyholder as to the appropriate gross profit to use for the BI calculation.

In relation to the stock valuation in the insured’s accounts, generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) [12] and international financial reporting standards (IFRS) mainly require that inventory be valued [13] using the lower of net realizable value [14] or cost.

Where there was both stock damage and BI following the UAE floods, in some instances there had been no attempt to address or reconcile the basis of stock valuation in conjunction with the rate of gross profit, resulting in an overlap between the BI and property damage claims. [15] This is an area which can be overlooked where the property damage aspect is seen to be the domain of the loss adjuster, and the BI to be that of the forensic accountant. It is important for there to be a joint approach to avoid this type of issue.

“Due Provision Being Made for Depreciation”

Depreciation is a controversial topic in business interruption insurance generally, with debates on both sides over whether it represents a savings [16] to be deducted from gross profit (e.g., where a machine is fire-damaged and written off, and subsequently replaced new-for-old by insurers, with the depreciation charge to the P&L ceasing or reducing as a result during the intervening period).

In this context, “due provision being made for depreciation” is generally understood to refer to redundant, obsolete, or slow-moving stock.

This may be confusing for two main reasons: 1) accountants would normally refer to “provisioning” or “write-off” in respect of stock/inventory, whereas the term “depreciation” is more commonly used when referring to fixed assets (e.g., plant and machinery); and 2) as laid out above, the opening and closing stock position per the insured’s accounts would inherently reflect this provisioning, in accordance with applicable accounting principles. To avoid potential confusion, as suggested in Riley, the policy wording may benefit from the deletion of the term depreciation in the context of stock.

Key Takeaways and Industry Lessons Post-Crisis

The unprecedented level of claims following COVID-19 and the 2024 storm in the UAE has highlighted an education gap, particularly in respect of business interruption insurance.

As outlined above, just the term “gross profit” can give rise to myriad issues. The same could also be said for others such as “turnover” or “trend.”

In relation to the disconnect between accounting and insurance gross profit, there have been suggestions in the past to insure on a gross revenue basis instead with a provision for deduction of savings (or non-continuing expenses), but this has not yet been widely adopted.

As a learning point, brokers need to ensure that the policyholder is informed of the various common pitfalls and misconceptions at the time of placement to ensure that adequate coverage is obtained. Too often this is by way of a template / workbook which is poorly explained or labeled for the insured to fill out, with a failure to check fundamental assumptions and inputs. Similarly, the policyholder needs to proactively engage in the process as opposed to simply obtaining figures from the accounts department on an annual basis or just rolling over the previous policy year after year.

For larger businesses, a full BI review (offered by major brokers, operational risk advisors, and/or forensic accountants) can be worthwhile to stress-test assumptions and potential loss scenarios.

Otherwise in the event of a claim, these are the types of issues which will need to be discussed and resolved to reach a business interruption settlement.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Daniel Thorpe for providing insights and expertise that greatly assisted this research.

References

[1] Riley on Business Interruption Insurance 11th Ed. Damian Glynn, Toby Rogers (2021); Sweet & Maxwell

[2] https://cila.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/BI-Wording-2024-Digital-FINAL-SECURED-.pdf

[3] Would also be closing balance for 31 December 2024 therefore could be tied back to year end audited financial statement (assuming financial year same as calendar year).

[4] Sometimes termed Specified Working Expenses.

[5] Definition of Turnover (also known as Sales, Revenue or Receipts) could be an article or articles in itself so will not be addressed in detail here.

[6] Which could be on a first-in-first out (“FIFO”) last-in-first out (LIFO) or average cost basis.

[7] The classic example (or “Eggsample”) is a conglomerate selling Faberge Eggs, Hens Eggs at different rates of Gross Profit (BI Cover Issues, Damian Glynn, November 2005; P.159 Clauses Clarifying the Core Cover). To take the example to the extreme, you could also extend this to include Embryos, Egg Whites, Egg Yolks, Pavlova, Easter Eggs etc all falling under the “Egg” department, which would be better served measuring gross profit on an even more granular level. There is usually no definition of what is meant by a department, other than a requirement for the segment(s) of the business to be able to generate independent ascertainable trading results. This is often somewhat debateable where revenue streams can be clearly separated (another Egg pun), but in order to arrive at “Gross Profit” the costs of the business inherently need to be separated or allocated across multiple products or processes, some of which may be common across all or some products or unique to others. The arguments for and against trying to apply a unique rather than blended rate can also depend on the circumstance of loss.

[8] There is some debate as to whether Uninsured Working Expenses in this context need to be conspicuously shown. Pursuant to Article 1028(c) of the UAE Civil Code, any clause designed to release an insurer from liability in given circumstances, for example an exclusion clause, is void unless “shown conspicuously”. The Insurance Law provides that such clauses should be identified in bold or different fonts or colours. Though failure to meet the formatting requirements under the Insurance Law does not automatically void such clauses, these requirements should be followed in practice to ensure compliance with the “conspicuous” requirements of the Civil Code.

[9] The Federal Tax Authority (“FTA”) was established under Federal Law by Decree No. 13 of 2016; The UAE published Federal Decree Law No. 8 of 2017 on Value Added Tax (“VAT”) on 23 August 2017, which came into effect on 1 January 2018.

[10] The exception being during Covid-19 where Dubai Decree 279 of 2020 regarding salary reductions, unpaid leave etc. was issued 26 March 2020 – a similar response to the UK’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (“CJRS”) otherwise known as “furlough” and South Africa’s Covid-19 Temporary Employee/Employer Relief Scheme (“TERS”).

[11] Other reasons can include taking a “backward looking” approach to setting the Sum Insured (i.e. looking at the last set of audited financials prior to policy inception) and/or failing to consider the trend of the business (remembering that you could have a 12-month (or longer) loss on the last day of the policy period).

[12] UK GAAP aligns more closely with IFRS.

[13] IAS 2.

[14] IFRS definition of net realizable value is estimated selling price less any reasonable cost associated with its sale, whereas GAAP refers to the best approximation of how much inventories are expected to realize.

[15] Property Damage/Business Interuption overlap could again be an article or articles in itself so will not be addressed in detail here.

[16] CILA have debated the subject on both sides (https://cila.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/depreciation-as-a-potential-saving.pdf) and there has been decisions in the UK (Synergy Health (UK) Ltd v CGU Insurance Plc [2010] EWHC2583 (Comm)) and Australian courts (Mobis Parts Australia Pty Ltd v XL Insurance Company SE [2018] NSWCA 342)