Introduction

As investment firms and public issuers contemplate adjustments in response to the evolving risk environment brought about by changes in federal securities enforcement priorities, one area of focus should be a likely expansion of state-level enforcement activity. State and territorial law enforcement agencies retain significant power under blue sky laws to investigate and enforce securities-related issues.

All 50 states, Washington DC and the territories of Guam, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands have blue sky laws and securities regulators. The first state blue sky law was enacted in Kansas in 1911 to prevent “speculative schemes which have no more basis than so many feet of ‘blue sky.’”

One of these laws’ functions is to regulate those securities left unregulated by federal authorities, such as securities only offered and sold within one state or offered by state or local governments. Another function overlaps with federal authority: preventing and punishing securities fraud.

Most state statutory definitions of securities fraud are substantially the same as that under federal law, which prohibits deceptive material statements and omissions in connection with securities transactions. The widely adopted Uniform Securities Act uses nearly identical language to that of Securities Exchange Act Rule 10b-5.1 However, that does not mean that the contours of what constitutes a "security" at the state and federal levels are identical.

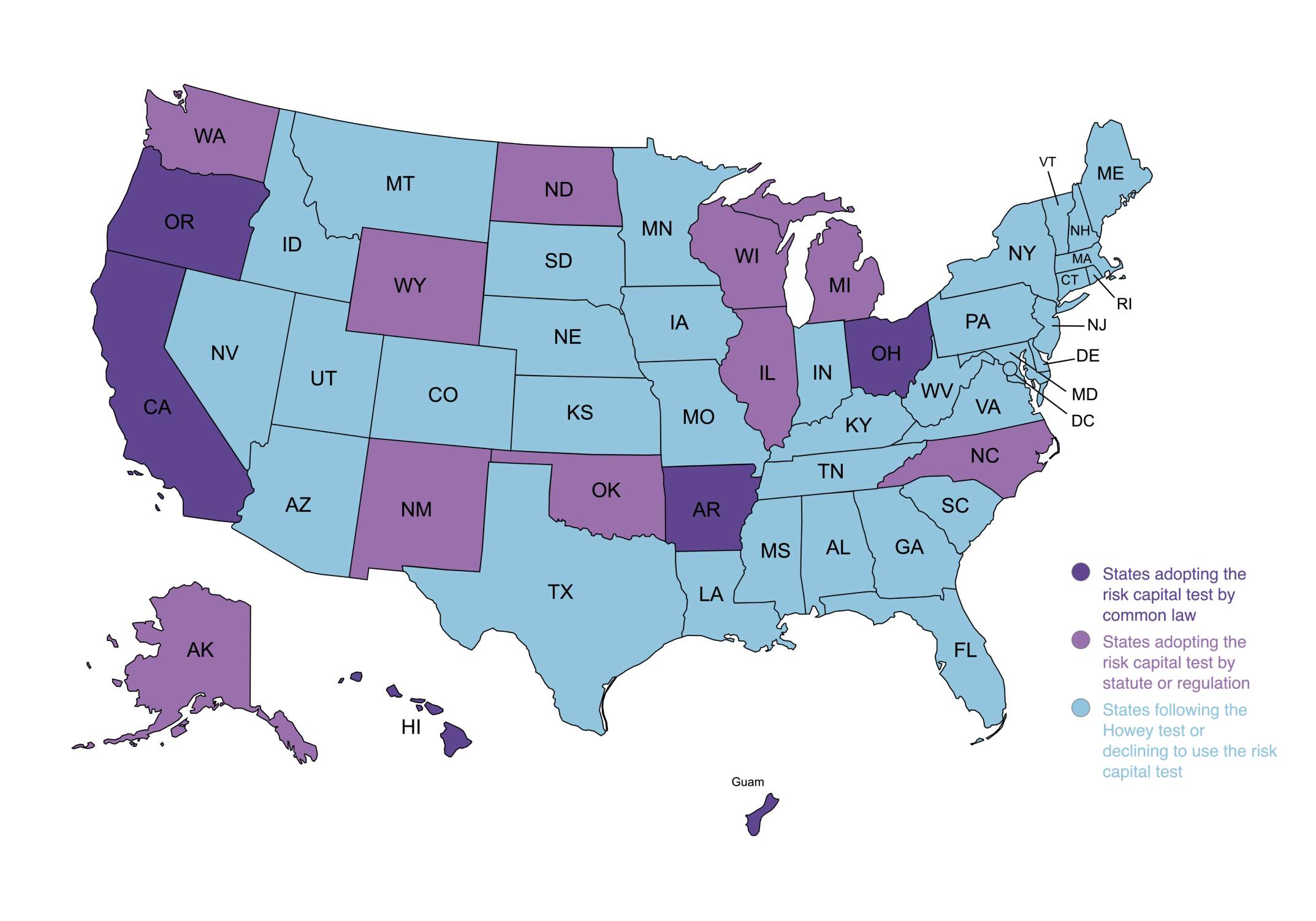

Most states have adopted the long-standing federal Howey test to determine whether an instrument is a security for purposes of state law. However, as states have become more active in exercising enforcement powers conferred by their blue sky laws, alternative legal tests have emerged. Most prominent among them is the risk capital test, which may capture more nontraditional instruments than the Howey test—potentially including certain cryptocurrencies.2 Awareness of how different states use their investigation and enforcement powers today is critical to navigating the complicated patchwork of securities laws going forward.

In this client alert, we will (i) outline the differences between the Howey test and the risk capital test; (ii) discuss enforcement activity by states utilizing the risk capital test, often to respond to perceived federal enforcement gaps; and (iii) review implications for issuers, broker-dealers and others in the financial industry.

Background: Federal Securities Tests Compared to the Risk Capital Test

Federal Tests for Securities

Before federal securities laws can be applied to a given instrument, a court must first answer a fundamental question: whether the instrument at issue is a “security” under federal law. For almost 80 years, federal courts have applied the Howey test, set forth in S.E.C. v. W.J. Howey Co., to evaluate whether an instrument is an investment contract and thus a security under federal law. Under Howey, an instrument is an investment contract and thus a security when there is (i) “an investment of money” (ii) “in a common enterprise” (iii) “with profits coming solely from the efforts of others.”3

Federal courts also apply a second test, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Reves v. Ernst & Young, to assess whether a note constitutes a security for purposes of federal securities regulation.4 Under the Reves test, a note is presumptively a security unless it “bears strong family resemblance” to a list of excepted instruments that are not securities.5

Risk Capital Test for Securities

While many states follow the Howey and Reves tests to determine whether instruments are securities, some states have adopted the risk capital test as either an alternative or a complement to these tests.6 One of the most prominent applications of this test comes from the 1961 case Silver Hills Country Club v. Sobieski, decided by the Supreme Court of California. In Silver Hills, Justice Roger Traynor applied the risk capital test to conclude that memberships sold to develop a country club constituted securities—the memberships involved an investment of money in an enterprise for profit, which subjects the investor’s money to the risks of the enterprise, and the investor has no managerial control over the enterprise.7 Traynor’s application of the risk capital test focused on the extent to which the investor’s funds were used as risk capital; “[o]nly because [an investor] risks his capital along with other purchasers can there be any chance that the benefits of club membership will materialize.”8

States have adopted and applied the risk capital test to varying degrees. The next section discusses those applications in more detail, with a focus on states with a greater volume of securities litigation.

States Applying the Risk Capital Test

In California, a security “is defined broadly by statute ‘to protect the public against spurious schemes, however ingeniously devised, to attract risk capital.’”9 While a security exists under the Howey test where there is an investment of money with an expectation of profit resulting from the efforts of others, California’s version of the risk capital test turns on whether an investor “risks capital.”10 Put differently, “the expectation of return on an investment, together with the right of repayment, does not—without more—subject the transaction to security regulation.”11 Instruments for which investors receive inadequate collateral to secure their investment have been held to be securities for purposes of California’s blue sky law.12 As a result, California’s securities laws empower its attorney general to bring securities fraud enforcement actions related to a variety of instruments, ranging from memberships in a country club,13 where the memberships were used to fund the construction and maintenance of the club, to fractional interests in an unsecured promissory note14 and a limited partnership.15

The Supreme Court of Oregon has also adopted the risk capital test.16 Oregon courts have found instruments and agreements similar to those considered securities under California law to be securities under Oregon securities law.17 A federal district court in Oregon has also applied Oregon law to determine that a security exists under Oregon state law—but not federal law—where an individual bought into a franchising scheme.18 In Stanley v. Commercial Courier Service, Inc., the court concluded that a franchisee provided the up-front risk capital for the franchisor to develop and operate the franchise.19 At the beginning stages of the franchise agreement—where the investor provided the initial risk capital but did not yet participate in a managerial role in the franchise—a security existed.

Oregon also provides a modern example of state attorneys general applying the broader risk capital test to treat newer instruments as securities. On April 18, 2025, Oregon’s attorney general, Dan Rayfield, brought an enforcement action against Coinbase, alleging that it was offering unregistered securities on its platform in violation of Oregon securities law.20 In his motions, Rayfield has highlighted that Oregon’s test to define a security “encompass[es] a broader range of investment schemes” than the federal Howey standard. Further, since bringing this action, Rayfield has stated publicly that “states must fill the enforcement vacuum being left by federal regulators who are giving up under the new administration and abandoning these important cases.” Coinbase is pushing back hard against the Oregon suit, arguing in its motion to dismiss that the attorney general lacks statutory authority to enforce the state’s securities laws, that the court lacks personal jurisdiction over Coinbase because it lacks minimum contacts in Oregon, and that the attorney general’s claims are time-barred.21 Coinbase characterizes the suit as “a flagrant intrusion on the province of federal law.”22

Further, the tension between the Oregon risk capital test and the federal Howey test has become an issue in Coinbase’s removal of the suit to Oregon federal court. Coinbase removed the case on the grounds that Oregon applies the Howey test—a construct of federal common law—and therefore gives the suit a basis for federal jurisdiction.23 The Oregon Attorney General, however, is seeking remand to state court, asserting that Oregon’s test differs from Howey and thus does not present a federal question.24 While this disagreement has yet to be ruled on in the case, this dispute importantly demonstrates that states’ non-Howey securities tests may influence questions of federal jurisdiction and defendants’ ability to remove cases to federal court, as well as the substantive legal arguments at the heart of the dispute.

Unlike the common-law risk capital test used in California and Oregon, Washington State has adopted the risk capital test by statute. RCW 21.20.005(17)(a) defines “security” to include an “investment of money or other consideration in the risk capital of a venture with the expectation of some valuable benefit to the investor where the investor does not receive the right to exercise practical and actual control over the managerial decisions of the venture.” Washington courts have interpreted this term to include arrangements such as limited partnership interests, given that an investor “puts his or her funds at risk and [the partnership] depends largely upon the managing partners’ efforts to realize a profit,” as well as certain general partnership interests.25

Michigan has similarly included the risk capital test in its definition of “security.” Under M.C.L. § 451.2102c(c)(i), contractual or quasi-contractual agreements constitute securities if they satisfy five elements, the second of which is that “[a] portion of the capital furnished . . . is subjected to the risks of the issuer’s enterprise.”26 Interpreting this subsection, the Michigan Court of Appeals held in People v. Mitchell that a vacation property lease was a security where defendants promoted the timeshare lease as an investment and expected investors to market the lease to prospective vacationers, in part because “each investor’s capital was subjected to the risks of the [defendants’] enterprise.”27 The Michigan Court of Appeals has also found that, while loan participation agreements and investments in a company’s accounts receivable both literally subject an investor’s capital “to the risk” of the underlying business or investment vehicle, this interpretation of the risk capital test would be overinclusive and produce absurd results.28 Instead, the court interpreted the risk capital test to include only those investments that are unsecured and found that, because neither agreement satisfied this test, neither was a security under Michigan state law.29

In Georgia, the legislature adopted the risk capital test in the Georgia Securities Act of 1973, which defined “investment contracts” in part as “an investment which holds out the possibility of return on risk capital even though the investor’s efforts are necessary to receive such return.”30 However, the Georgia Supreme Court applied the Howey test six years later in Dunwoody Country Club of Atlanta, Inc. v. Fortson, ultimately holding that a country club membership that issued a “redeemable membership certificate” worth either $600 or $1,200 was not a security under Georgia law.31 Further, assuming without deciding that the Georgia legislature adopted the risk capital test, the court concluded that the membership would not constitute a security under that test either.32 In 2008, Georgia adopted the Uniform Securities Act, thereby removing any references to the risk capital test in the state’s definition of “security.”33

At bottom, states employing the risk capital test—which focuses on the risk to an investment rather than the expectation of profits—may use their blue sky laws to regulate instruments that federal securities laws (and the Howey test more broadly) do not reach.

Implications

The distinctions between the Howey and risk capital tests are important on their own terms because they may lead to different results in state versus federal litigation on securities issues and may impact the availability of federal court removal for matters involving interpretation of state securities laws; however, the current polarized political environment seems likely to exacerbate the impact of the Howey/risk capital distinction. Given the Trump Administration’s pro-crypto34 and wider deregulatory35 policy agenda, Democratic state attorneys general and securities regulators36 may use state securities enforcement powers to act as a counterweight and/or to advance their own political priorities.37

Financial industry firms, exchanges, issuers and others should consider the potential impact of the Howey/risk capital distinction as they face what may be a more fractured securities regulatory environment in coming years. WilmerHale’s experienced securities litigation and enforcement, securities regulatory, and state attorneys general practice groups stand ready to assist in scoping and addressing risks that this new environment may present.38

Footnotes