Image: Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) with AI.

Image: Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) with AI.

Abstract

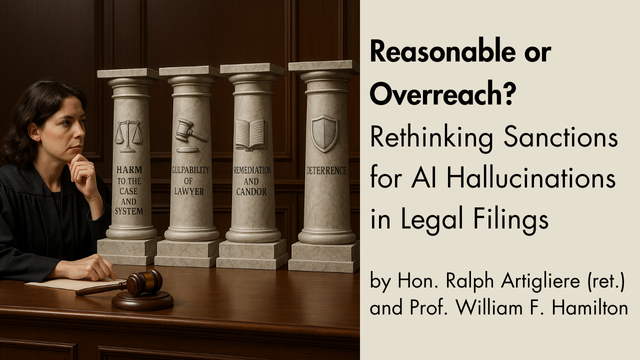

This article examines the problem of fabricated or hallucinated citations in legal briefs, focusing on the recent federal decision in Johnson v. Dunn as a case study. That decision highlights the risks when lawyers rely on generative AI without adequate verification. This article analyzes the unique challenges posed by AI hallucinations, emphasizing the importance of distinguishing between reckless misconduct and honest mistakes, and explores whether harsh sanctions are justified given the typically minimal substantive harm in such cases. It argues that sanctions for such errors must be principled, proportionate, and consistent with existing jurisprudence and proposes a four-pillar framework for judges to evaluate AI-related citation misconduct, balancing the need to deter careless practice with the imperative to preserve fairness and encourage responsible use of valuable new technology.

In Johnson v. Dunn,1 a Northern District of Alabama federal judge sanctioned three experienced attorneys for submitting two motions containing five erroneous citations generated by ChatGPT. The case, analyzed in a previous article by one of the authors,2 is an escalation in the judiciary’s handling of errors created by generative AI moving beyond fines and reprimands to applying sanctions causing reputational damage with potential career-altering consequences.

AI hallucination incidents are increasing,3 and they require serious attention.4 However, whether severe, public sanctions are the appropriate solution deserves careful consideration, especially when case-specific harm is minimal. What distinguishes citation hallucinations from other legal errors? And why did their appearance in Johnson v. Dunn lead to such broad penalties?

We argue that future judicial responses to AI-related citation errors should be guided by measured professional judgment. In exploring this question, we address:

- Whether judicial reaction to hallucinations is outpacing actual harm;

- The role opposing counsel should play in raising or resolving citation errors; and

- How a principled, repeatable framework can guide sanction decisions without unnecessary overreaction.

Sanctions should remedy wrongs, deter future misconduct, and protect the integrity of the justice system while remaining fair to all parties and participants. A calibrated approach protects litigants, conserves judicial resources, and achieves true deterrence without overreach.5

Context and Controversy: What Happened in Johnson v. Dunn

In Johnson v. Dunn, three experienced litigators6 from a prominent national law firm were sanctioned for submitting two motions that contained five fabricated case citations generated by ChatGPT. Opposing counsel flagged the citation anomalies in their responses, prompting the court to independently verify the errors. Following a show cause order and a hearing with all attorneys involved, the U.S. District Judge imposed sanctions on the three lawyers connected to the filings.

Citing its inherent authority,7 the court found that each attorney’s conduct was “tantamount to bad faith.” The resulting sanctions were severe: public reprimands, disqualification from the case, referrals to the Alabama State Bar, and an unusual order requiring each sanctioned attorney to provide the sanctions order to every client, colleague, opposing counsel, and presiding judge in active matters.

The resulting sanctions were severe: public reprimands, disqualification from the case, referrals to the Alabama State Bar, and an unusual order requiring each sanctioned attorney to provide the sanctions order to every client, colleague, opposing counsel, and presiding judge in active matters.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

In her order, Judge Manasco acknowledged that these sanctions exceeded those imposed in earlier AI hallucination cases.8 Nonetheless, she emphasized that the court’s inherent authority supports sanctions not only to rectify misconduct, but also to deter future violations9 and preserve judicial integrity. As she put it:

The court further finds that no lesser sanction will serve the necessary deterrent purpose, otherwise rectify this misconduct, or vindicate judicial authority.10

By presenting these rationales in the alternative, the court left unclear which factor primarily justified the stiffer penalties. This ambiguity matters. As we’ll discuss below, only one of the three sanctioned attorneys knowingly used ChatGPT. The other two were found to have failed in their supervisory duties but were unaware that AI was used to generate content in the motions. The motions did not misstate the underlying law; the only errors were the citations themselves. The opposing party suffered no substantive prejudice. Had the court limited its response to awarding costs or fees for the extra work caused by the errors, it would have aligned with existing precedent in similar cases.

That leaves deterrence and “vindicating judicial authority,” two expansive rationales, as the principal justifications. The role each attorney played and how these fabricated citations made their way into the final filings informs the analysis of whether these justifications warrant such sweeping sanctions.

Dropping the Ball Despite Safeguards

How could these erroneous submissions happen in a nationally prominent firm with written AI policies, an Artificial Intelligence Committee, and seasoned litigators? The underlying litigation was high-stakes prison constitutional violation litigation for the State of Alabama. Yet the two motions at issue, a motion to compel and a motion for leave to depose a party, were routine discovery filings.

The two motions containing hallucinated citations generated by ChatGPT were prepared by two of the firm’s lawyers and reviewed by a third. The three lawyers had experience working together. One was of counsel to the firm, the second was a partner and assistant practice group leader in the firm’s constitutional and civil rights litigation group, and the third was a partner and practice group leader of the constitutional and civil rights litigation group.

The drafting process was routine and familiar. One attorney (the of counsel drafting lawyer) prepared the initial drafts and forwarded them for review. A second attorney (the reviewing lawyer, a firm partner and an assistant practice group leader) revised the drafts and added content. Critically, that new content included citations generated by ChatGPT, which he did not verify through Westlaw, PACER, or any other authoritative source despite firm policy prohibiting such unsupervised use. He later admitted this was the first and only time he had used ChatGPT for legal drafting and acknowledged it was a serious error in judgment.

Critically, that new content included citations generated by ChatGPT, which he did not verify through Westlaw, PACER, or any other authoritative source despite firm policy prohibiting such unsupervised use. He later admitted this was the first and only time he had used ChatGPT for legal drafting and acknowledged it was a serious error in judgment.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

A third attorney (the responsible lawyer), a firm partner and the practice group leader, reviewed only the motion to compel, giving it a brief scan focused on factual background, headings, and substantive argument. He did not check the citations or know that ChatGPT had been used.

When the reviewing lawyer returned his edits, the drafting lawyer checked them for factual accuracy, grammar, and style, but not for the accuracy of the citations. He signed and filed the motions, later acknowledging that by doing so he accepted ultimate responsibility for their content, even though he had no reason to suspect that a partner’s edits were noncompliant with firm standards.

In response to the court’s show cause order, the firm and all three attorneys admitted the ChatGPT citations were wrong and sanctionable. The reviewing lawyer even urged that he should bear sole responsibility, given that he had injected the faulty citations into the motions.

How Could this Mistake Happen?

The reasons for submitting hallucinated citations are varied. A lawyer may not appreciate that an LLM is merely a prediction machine capable of making confident but false connections. Most general-purpose LLMs excel at “chat language”—polished, convincing, and delivered with unwarranted certainty. Lawyers may plan to verify citations later, only to have that step lost in the pressures and urgency of litigation. In team settings, miscommunication can occur when each lawyer assumes another is checking the citations. None of this is excusable, but it falls short of malevolence.

The solution is deceptively simple: check the citations. Commercial legal platforms such as Lexis and Westlaw include robust citation verification tools,11 and every lawyer has access to manual verification methods. But the simplicity of a solution does not convert a missed step into an intentional or corrupt practice. Just because a solution is simple does not mean that failing to apply it is an unequivocal sign of gross dereliction. Straightforward safeguards may be missed without malice, and such lapses should not automatically trigger the most severe sanctions. And for the lawyers who were in a reviewing or supervising role, their conduct must be assessed understanding that they had no reason to expect AI was used in revisions by one of the team.12

Straightforward safeguards may be missed without malice, and such lapses should not automatically trigger the most severe sanctions.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

Was the Behavior of All Three Recklessness Tantamount to Bad Faith?

The record shows no intent to deceive or to gain an unfair advantage, only a breakdown in communication and verification. The lawyers’ roles and knowledge were not interchangeable. Two had no idea ChatGPT was used, and each relied, in different ways, on the assumption that experienced colleagues were meeting the same professional and firm standards they themselves followed.

Certainly, a lawyer who signs a filing is responsible for its contents. But is it recklessness tantamount to bad faith to rely on an experienced partner’s edits without rechecking every citation? Similarly, should a practice group leader be sanctioned at that level for failing to spot-check citations in a routine motion prepared by trusted subordinates?

The reviewing lawyer’s conduct of using ChatGPT in defiance of firm policy and failing to verify the output was unquestionably wrong. Yet, does that error, in the context of immediate admissions, an absence of prejudice to the opposing party, and the availability of narrower remedies, truly rise to the “bad faith” threshold? Even where sanctions are merited, a court should impose the least severe sanctions necessary to achieve the goal where the purpose of imposing sanctions is deterrence.13

Of course, if an avalanche of hallucinations were causing a breakdown and dysfunction of our judicial system, the problem should be sternly addressed. However, are the numbers of reported hallucination cases14 that shocking given the literally millions of annual filings in federal and state courts and the increasingly widespread use of generative AI? The courts must respond, but proportionality matters.

Judges, like lawyers, sign off on others’ work and are accountable for errors — yet their own citation mistakes are rarely treated as bad faith. Sanctions should fit the harm and culpability, not reflexively reach for the harshest penalty.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

The court’s concern over hallucinated or erroneous citations is legitimate, but proportionality matters. Judges themselves have, on occasion, withdrawn orders after discovering factual or citation errors — sometimes tied to staff work or unauthorized AI use.15 Those mistakes, while damaging to public confidence, are generally not treated as recklessness tantamount to bad faith. Judges remain fully responsible for what they sign, regardless of whether the inaccuracy came from counsel, staff, or technology.16 This comparison is not to excuse lawyer misconduct, but to show that such errors, wherever they originate, call for sanctions tailored to culpability, harm, and deterrence — not the harshest penalties available.

From Case Study to Guiding Principles

The Johnson v. Dunn decision offers a vivid, and controversial, example of a court responding to AI-related citation misconduct. It also reveals a risk. When judicial concern about emerging technology is not grounded in careful precedent, fears can be exaggerated, precedents can be discounted, and sanctions can shift toward serving a broader indiscriminate and likely ineffective “messaging” purpose rather than fitting the specific misconduct. The result can be confusion among practicing attorneys and a chilling effect on the use of valuable tools and technology by firms and their lawyers. It may also trigger a trend of harsher sanctions in subsequent cases.17

When judicial concern about emerging technology is not grounded in careful precedent, fears can be exaggerated, precedents can be discounted, and sanctions can shift toward serving a broader indiscriminate and likely ineffective “messaging” purpose rather than fitting the specific misconduct.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

Consider the more measured response in In re Martin,18 decided just two weeks earlier on July 18, 2025. There, a bankruptcy attorney filed a brief containing fabricated quotations and non-existent authorities generated by artificial intelligence. The lawyer accepted responsibility, expressed remorse, and withdrew the brief. After reviewing multiple hallucination cases,19 including some also discussed in Johnson,20 the court ordered the attorney and a senior partner to attend a specialized national AI training program for bankruptcy practitioners and imposed a $5,500 fine.

Likewise, in Lacey v. State Farm,21 decided on May 5, 2025, U.S. Magistrate Judge (ret.) Michael Wilner, sitting as a special master, faced a situation factually similar to Johnson. The plaintiff, Mrs. Lacey, was represented by a large team of attorneys from two nationally prominent firms. In preparing a submission to Judge Wilner, one lawyer used content from generative AI that included numerous erroneous citations and legal authorities. Even after Judge Wilner specifically asked for clarification on two of the citations, the resubmitted document corrected only those two, leaving other erroneous citations in place.22

Judge Wilner applied Rule 11 and inherent authority sanctions but limited them to denying the relief the plaintiff requested23 and awarding $31,000 in attorney’s fees and costs to be paid by the law firms. He explained his reasoning for not sanctioning the individual attorneys, including the reviewing lawyers and the attorney who used AI:

In a further exercise of discretion, I decline to order any sanction or penalty against any of the individual lawyers involved here. In their declarations and during our recent hearing, their admissions of responsibility have been full, fair, and sincere. I also accept their real and profuse apologies. Justice would not be served by piling on them for their mistakes.24

As in Johnson, the declarations and responses in Lacey included genuine apologies and honest admissions of fault. Yet Judge Wilner chose not to even name the individual lawyers in the order and exercised restraint in considering the professional impact of sanctions.

The conduct in Martin and Lacey was strikingly similar to Johnson, but the sanctions were far less severe. Differences in courts, case types, and procedural contexts can justify some disparity. However, as in Lacey, two of the lawyers in Johnson had no knowledge that AI had been used, and the conduct of the third attorney did not materially differ from that of the attorney in Martin. In fact, the lapses in supervision and citation checking in Lacey could be viewed as more serious than the attorneys in Johnson.

Not all judges see AI-related citation errors as warranting the most severe sanctions. Hon. Xavier Rodriguez of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, quoted recently in MIT Technology Review, offered this perspective:

I think there’s been an overreaction by a lot of judges on these sanctions. The running joke I tell when I’m on the speaking circuit is that lawyers have been hallucinating well before AI. Missing a mistake from an AI model is not wholly different from failing to catch the error of a first-year lawyer. I’m not as deeply offended as everybody else.25

The disparity in sanctions between Johnson and other similar cases underscores the need for a principled, repeatable framework for evaluating AI-related citation errors. Such a framework should preserve judicial integrity while calibrating sanctions to the actual harm, degree of culpability, and remedial actions taken. A “four-pillar” framework can help strike that balance.

A Framework for Hallucination Sanctions: A practical four-pillar test judges can apply

The following framework (or scorecard) proposed by the authors is a sanctions proportionality matrix. When applying the matrix score, each pillar should receive a High, Medium, or Low score that is explained by the court. Sanctions escalate when scores across multiple pillars are High.

1) Harm to the case and system

- Case prejudice (delay, expense, lost merits opportunity)

- Systemic harm (required excessive court time, damaged public confidence, required record correction)

- Contamination (did the error propagate into other filings or rulings?)

2) Culpability of each lawyer

- Knowledge/intent (submitter knew or should have known; ignored firm policies or court guidelines)

- Role-specific duty (signer’s non-delegable Rule-like duty; supervisor’s oversight; drafter’s verification)

- Prior notice/training/policies (clear warnings; explicit bans; prior incidents)

3) Remediation and candor

- Speed and completeness of correction (self-report vs. opponent-revealed)

- Scope of remedial audit (single document vs. firm-wide; the utilization of outside validation audit)

- Cost shifting (payment of incurred fees and costs of the non-offending party)

4) Deterrence context

- Recency and frequency (pattern vs. one-off)

- Alternative, narrower remedies available (targeted education, fee award, filing restrictions)

- Collateral effects (impact on other clients uninvolved in the case; reputational impact beyond impacted cases)

The Sanctions Ladder that Maps to the Four Pillar Test

- Low/Medium overall: corrective filing; fee shifting; written admonition; mandatory CLE.

- Medium/High: public reprimand; targeted publication to parties in the case; limited filing restrictions in the case.

- High: removal from the case; court-specific practice suspension; bar referral.

- Extreme (multiple Highs with aggravators): broader suspension or referral with interim restrictions.

Drawing from established sanctions jurisprudence under a court’s inherent authority, and professional responsibility standards, let’s apply the four-pillar test in Dunn v. Johnson.

1. Harm to the Proceeding or the Parties

- Johnson v. Dunn involved fabricated citations, but the underlying law was not disputed, the motions were routine discovery requests, and opposing counsel was not materially disadvantaged beyond the work of identifying and pointing out the errors.

- Rationale: Courts should distinguish between AI-related errors that actually mislead the court or prejudice a party, and those that are promptly corrected with minimal substantive impact. The guiding question should be: Did the AI-generated error meaningfully alter the court’s decision-making or burden the opposing party beyond correcting the error?

2. Culpability and State of Mind

- In Johnson v. Dunn, only one attorney knowingly used ChatGPT, and he admitted the conduct was contrary to firm policy and professional obligations. The other two relied on his edits without knowledge of AI involvement.

- Rationale: Sanctions law recognizes a spectrum from negligence to recklessness to bad faith.26 Recklessness tantamount to bad faith justifies harsher measures; mere negligence typically does not.

- The guiding question should be: Was the misconduct the result of intentional disregard, reckless indifference, or an understandable (though sanctionable) lapse?

3. Remediation and Cooperation

- After discovery of the errors, the Johnson v. Dunn attorneys admitted fault, apologized, and the firm undertook extensive remedial steps, including reviewing 2,400 citations in 330 filings across 40 federal dockets, finding no other fabricated citations.

- Rationale: Sanctions analysis should account for whether the lawyer or firm took prompt, good-faith action to correct the record, cooperate with the court, and prevent recurrence. The guiding question should be: Did the response demonstrate acceptance of responsibility and genuine efforts to fix the problem?

4. Deterrence and Proportionality

Courts have a wide variety of sanctions available for the purpose of deterrence, but the court should use sanctions that are limited to what suffices to deter repetition of the conduct or comparable conduct by others similarly situated.27

- The Johnson v. Dunn court justified its sanctions as necessary to deter future misconduct and “vindicate judicial authority,” even though prior cases imposed far less severe penalties for similar AI-related errors.

- Rationale: A deterrence rationale is valid, but sanctions should be calibrated so they are neither symbolic overreach nor a mere “cost of doing business.” Disbarment level penalties should be reserved for misconduct with high malevolence and actual harm. The guiding question should be: Is the sanction proportionate to the harm and culpability, and will it deter future violations without chilling legitimate advocacy or technology use?

Why This Matters

Applied to Johnson v. Dunn, our four pillar framework might have led to reduced and differentiated sanctions—still meaningful, but tailored to each lawyer’s role, knowledge, and actions. Going forward, courts can use these pillars to ensure AI-related sanctions are consistent, fair, and aimed at the right target: protecting the integrity of the justice system without reflexively imposing career-altering penalties for every hallucination incident.

All Hands on Deck: The Role of Opposing Counsel

Proportionality in sanctions begins before the court ever gets involved. In Johnson v. Dunn, opposing counsel identified the erroneous citations in the submissions. How might they have responded other than by calling out the errors in their response memorandum to the court?

The legal system works best when all participants, including counsel on both sides and the court, accurately identify the law governing the case. Opposing counsel’s first obligation is to their client, but professional courtesy and efficiency favor raising citation errors promptly and directly with the other side when circumstances allow. Often, a phone call or email can resolve the issue faster, more cheaply, and without lasting damage to reputations. In many cases, a cooperative fix preserves credibility on all sides and avoids unnecessary motion practice. There is a difference between protecting your client’s interests and turning an error into a public spectacle when it could otherwise be corrected quickly.

Opposing counsel’s first obligation is to their client, but professional courtesy and efficiency favor raising citation errors promptly and directly with the other side when circumstances allow. Often, a phone call or email can resolve the issue faster, more cheaply, and without lasting damage to reputations.

Hon. Ralph Artigliere (ret.) and Professor William F. Hamilton.

Of course, not all errors can or should be handled informally. Where an error is repeated, ignored,28 or causes material prejudice, formal court involvement is justified. But when an isolated, admitted mistake can be remedied without impairing the client’s case, immediate escalation to sanctions invites disproportionate outcomes and undermines the profession’s cooperative norms.

Courts, too, benefit from a cooperative approach. When opposing counsel and the filing attorney resolve errors early, judicial resources are preserved for disputes that genuinely require adjudication. Sanctions then become a tool of last resort, reserved for bad faith, repeated violations, or conduct causing real harm—not an inevitable consequence of every lapse.

Closing Note for All Lawyers

AI is here to stay—but so are your professional duties. Don’t trust, verify. Whether the source is ChatGPT, a premium legal AI tool, or a colleague you’ve known for twenty years, the rule is the same: open the case, read it, confirm it, and make sure it says what you claim it says. That’s how you protect your client, your license, and the integrity of the justice system.

For Practitioners

- Treat general-purpose LLMs (e.g., ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot) as brainstorming tools only—never for citations.

- Even with legal-specific AI tools, verify every assertion: open the case, confirm the proposition, check controlling status, and review subsequent history.

- Teamwork protocols:

- Clarify responsibilities for adding and verifying citations.

- Log who added each citation, how and when it was checked, and by whom.

- Before signing, review the log, sample-check cites, and require verification notes.

For Opposing Counsel

- Verify the other side’s citations when drafting responses—don’t assume accuracy.

- Raise errors promptly but professionally; a direct phone call or email may resolve the issue without court involvement.

- Document discovery of citation errors and any resolution attempts to preserve the record.

- Consider whether a motion is necessary, or whether corrective action short of judicial intervention will protect your client.

For Courts

- When hallucinations appear, focus first on the case-specific harm and the responsible party’s intent, not the broader tech trend.

- Distinguish between bad-faith misuse and negligent oversight; calibrate sanctions accordingly.

- Consider remedial orders—such as costs, education, or monitored filings—before imposing career-altering penalties.

- Apply consistent standards so similar conduct results in similar consequences, regardless of public attention or AI involvement.

For Law Firms

- Establish clear AI use policies: define approved tools, prohibited uses, and verification protocols.

- Train all attorneys and staff on AI’s risks, including hallucinations and confirmation bias.

- Require verification logs for all filings; mandate at least one independent citation check before submission.

- Hold everyone accountable—from junior associates to practice group leaders—for ensuring accuracy and compliance with firm policy.

- Audit compliance periodically to ensure policies are being followed in practice.

CONCLUSION

Johnson v. Dunn illustrates both the challenges and the stakes of AI-related misconduct in legal filings. The court’s sanctions were unquestionably severe, more severe than in prior hallucination cases such as Mata v. Avianca, In re Martin and Lacey v. State Farm, and they raise important questions about consistency, proportionality, culpability, and deterrence. While protecting the integrity of the judicial process is paramount, sanctions that overshoot the facts and intent risk undermining fairness and chilling responsible technology use.

Ultimately, sanctions for AI-related citation errors should fit the misconduct and the moment. Proportionality protects both the integrity of the judicial process and the fairness owed to practitioners navigating new technological terrain.

The four-pillar framework we propose—harm, culpability, remediation, and proportionality—offers courts a principled way to separate egregious, bad-faith misuse of AI from sanctionable but less culpable errors. Applied consistently, it can ensure that sanctions remain calibrated to the specific misconduct, that penalties deter without destroying careers unnecessarily, and that justice is served without yielding to institutional overreaction or public alarm.

The legal profession’s challenge is not to fear AI, but to master it responsibly. Judges, lawyers, and firms all have roles to play in setting clear expectations, verifying accuracy, and fostering a culture where technology is a tool, not a shortcut. Meeting that challenge can help us avoid the next Johnson v. Dunn, not by luck, but by design.

Notes