For US-listed public companies, issuing corporate guidance can feel routine—until it isn’t. One overly rosy forecast or offhand comment on an earnings call can turn into plaintiffs’ or regulators’ Exhibit A. For companies that issue guidance and management teams that present the information, the challenge is this: How do you communicate confidence without creating liability? In this article, my colleague, Lenin Lopez, explores some ways to strike the right balance and steer clear of regulatory and litigation traps. —Priya Huskins

Ironically, the more clarity US-listed public companies try to give the market in the form of guidance, the murkier their legal risks may become. If actual results don’t align, particularly if they fall short, it can open the door to second-guessing of the management team and board, as well as Monday morning quarterbacking by analysts, regulators, and plaintiffs’ firms.

This article will discuss trends in how companies are approaching corporate guidance, examine litigation and enforcement activity, and share practical takeaways. We’ll explore how executives can respond when they can’t fully discuss key metrics or business drivers—especially when analysts are trying to back into financial details the company hasn’t disclosed.

A Brief History of Time Guidance

As a reminder, issuing corporate guidance isn’t required. That said, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) created a safe harbor in the 1970s that provided some legal protection for companies that voluntarily disclosed projections, as long as they had a reasonable basis for those projections and related statements, and disclosed them in good faith.

Fast forward a couple of decades and many public companies that were making forward-looking statements—statements that evidence management’s beliefs about what the future holds (e.g., guidance)—were finding themselves at risk of being dragged into expensive securities lawsuits based simply on stock price drops and allegations that the drops were the result of overly optimistic statements made by the company.

To curb these types of frivolous lawsuits, Congress passed the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act (PSLRA) in 1995. The PSLRA provides that certain forward-looking statements can’t form the basis of a claim of fraud if specified conditions are met. One of those conditions is the disclaimer language that management teams that speak to the street know too well. It takes the form of the canned statement read at the beginning of earnings calls, investor days, or included at the end of earnings releases or other company disclosures where forward-looking statements are made by the company.

In addition to the PSLRA, companies have the benefit of additional guardrails in the form of a steady stream of guidance resources published by the SEC.

Companies have generally been consistent in providing some level of insight into how they may perform in the future, whether that is on a quarterly, annual, qualitative, or quantitative basis.

A Shift Toward Tempered or No Corporate Guidance?

All said, it’s more common for public companies to provide guidance than not, and analysts have come to expect it. The form of that guidance, however, can vary significantly. For instance, some companies provide earnings guidance, while others only provide sales guidance, or guidance specific to capital expenditures and cash flow, and the list goes on.

It’s likely a surprise to no one that during the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant number of companies chose to stop issuing guidance altogether. An uncertain operating environment, lockdowns, and unprecedented changes in how society functions will do that.

With what happened because of COVID-19, one would expect the ongoing kerfuffle over the US tariffs regime to lead to a repeat wave of companies choosing to withdraw guidance. For some, that has been the case, but for many S&P 500 companies, it’s business as usual when it comes to issuing guidance.

It’s important to note that during and after the COVID-19 era, companies across industries chose to resist the pressure to guide precisely. Instead, many now provide narrative commentary or broad ranges—an approach better suited to the current operating environment, which has been and continues to be characterized by evolving regulatory and political dynamics, longer commercialization runways, and so much more.

As an example, we have seen life science companies increasingly issue milestone-driven updates tied to clinical trials or US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) engagement, rather than revenue forecasts. Artificial intelligence and semiconductor companies, meanwhile, may offer qualitative guidance reflecting customer demand and capacity trends, rather than committing to specific quarterly bookings or earnings.

This pivot to a more cautious approach may be attributed, in part, to some companies getting punished by the market after guidance surprises that led to stock price drops, and plaintiffs’ firms filing securities class action lawsuits as a result.

Litigation and Enforcement: Guided into Trouble

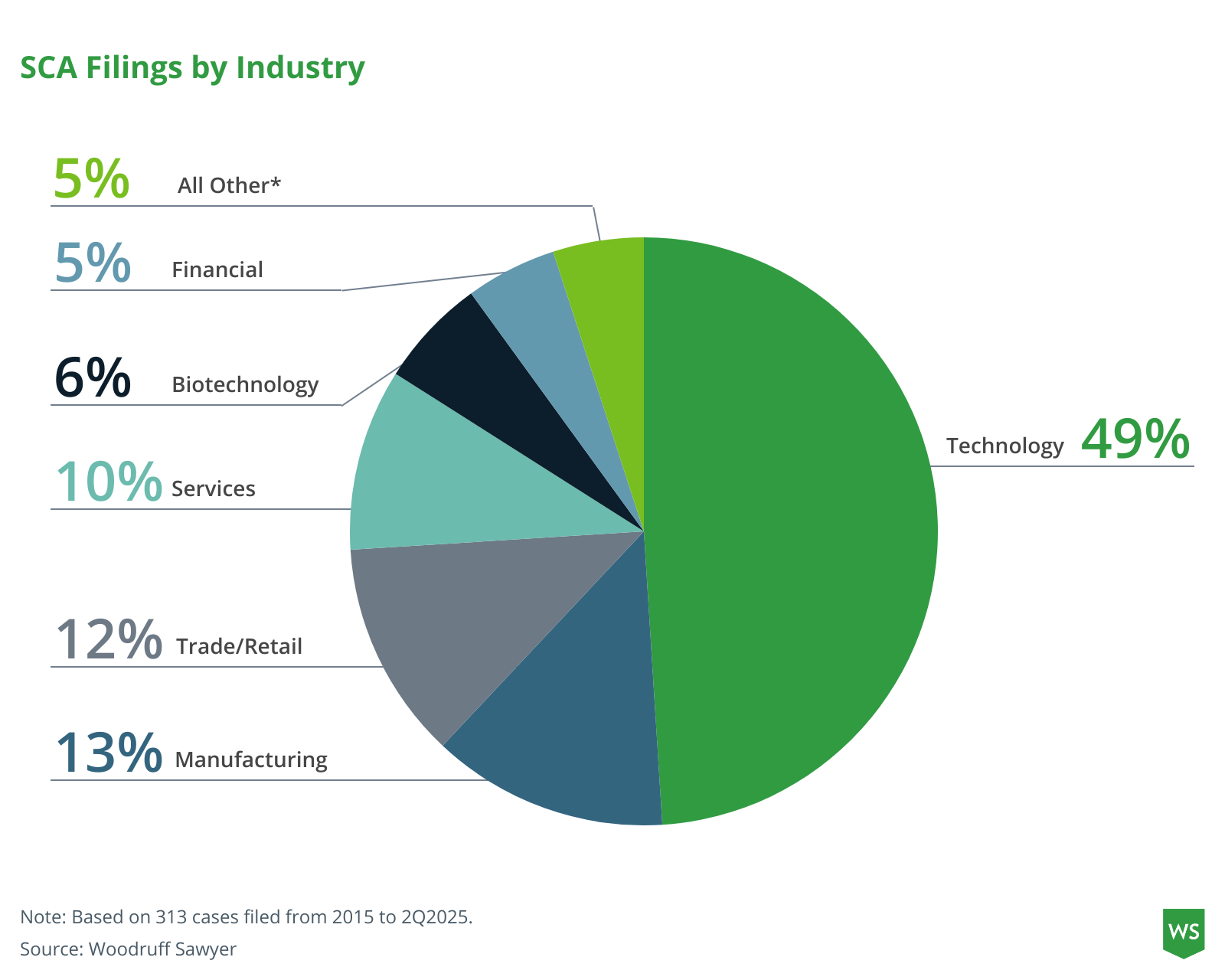

Our 10-year review (2015 to 1H 2025) of securities class action filings shows a few telling patterns when it comes to guidance:

- In securities class action lawsuits involving allegations of misrepresentations of revenue growth, 36% of those suits involved companies that had disappointing financial results.

- 40% of those suits involved a lowering or withdrawal of guidance.

.png)

In other words, when a revenue story cracks and is followed by a forecast revision, plaintiffs often allege that earlier statements were materially misleading. This dynamic is a particular issue for companies in the tech industry—industries where valuation often hinges on projected growth rather than current results.

And the SEC is still paying attention. Yes, there are news stories about how the SEC under Chairman Paul Atkins will be marked by a pullback on rulemaking and a change in enforcement priorities whereby novel theories, like shadow trading, may not be the basis for enforcement actions. However, it’s clear that the SEC will continue to pursue “bread and butter” disclosure failures and misleading forward-looking statements—especially in high-growth sectors built on future promise. This means that disclosure issues involving guidance will likely continue to be on the SEC’s radar and perhaps even more so than in the last four years.

Risky Seasons: Real-World Examples

Enforcement actions and securities class action lawsuits often cluster around certain pressure points in a company’s lifecycle—times when future financial visibility is low and expectations are high. In tech, semiconductor, biotech, and life science, these moments often hinge on a few pivotal catalysts, making even small misses costly.

After an IPO, for example, a newly public semiconductor company may feel compelled to project aggressive margin expansion to satisfy analyst models. But without a track record, short-term visibility can be clouded by volatile demand signals, leading to sharp market reactions—and in some cases, claims that management should have tempered its tone.

Macroeconomic headwinds can be just as hazardous. A chipmaker, confident in certain data, might miss early signs of inventory buildup. When sales slow and guidance is cut mid-cycle, investors often argue that the slowdown was foreseeable.

Product commercialization is another high-risk period. A biotech company forecasting substantial launch-year revenue from a newly approved therapy may not fully account for payer negotiations or physician adoption delays. If those factors push revenue recognition out by a quarter or two, plaintiffs’ firms may claim the original guidance ignored known hurdles.

Across these scenarios, the common thread is unnecessary over-precision in the face of uncertainty. Companies that face similar inflection points should consider weighing whether narrative or range-based guidance—anchored in disclosed risks—might better protect credibility and mitigate legal exposure.

Best Practices & Key Takeaways

Regulators and plaintiffs’ firms know where to look for their next case—and guidance is the prime hunting ground. They comb through earnings releases, earnings call transcripts, investor decks, and other company disclosures for statements that can be recast as misrepresentations of actual performance. Even a small disconnect between guidance and subsequent results can be framed as evidence that management overstated performance, ignored known risks, or failed to disclose material information.

The following are considerations that may help management teams deliver meaningful insight into the company’s future performance while limiting the likelihood of catching the ire of regulators and plaintiffs’ firms.

Maintain Discipline When Speaking with the Street

Analysts often try to back into undisclosed metrics by asking seemingly innocuous questions. Once disclosed, those figures can, among other things, reset market expectations.

For earnings calls and/or discussions with analysts and investors, here are a few examples of how management may respond to deflect, redirect, and maintain consistency without appearing evasive.

Q: Regarding metrics or guidance the company hasn’t historically provided

- “While we do not provide guidance by segment or on a quarterly basis, let me offer some qualitative considerations to support your modeling.”

- “We don't provide guidance for individual quarterly periods. There's certainly a range of outcomes, and we'll have a better read on how we will compare as we progress through the year.”

Q: Regarding competitors or peers

- “I can’t comment on others, but our focus continues to be helping customers through [whatever uncertainty or complexity they are facing].”

- “I can't comment on our peers and the challenges that they might be facing. But what I can say very clearly is our business is [significantly more diversified than those you are talking about].”

Q: Regarding any general topic that the company would prefer not to respond to

- “Consistent with prior calls, I can’t speak to the details around…”

- “Let me start with what I can tell you now. First, let me remind you, it's very early in this process. We have begun to [investigate what the cost and the work scope and the timing might be, but there'll be some learnings over the next 30 to 60 days], and we'll certainly come back and talk to you a little bit about that.”

Favor Qualitative or Range-Based Guidance Over Point Precision

When uncertainty is high, precision can become a liability. Narrative guidance like “mid-teens revenue growth, assuming regulatory clearance in Q3” or ranges offers flexibility while still providing the investment community with insights into how the company views future performance.

Build Guidance on a Robust and Documented Set of Support

Ideally, modelling should incorporate plausible risk factors, like supply chain hiccups, tariff regime changes, regulatory delays, and reimbursement timelines, as well as stress-testing upside and downside scenarios. Documenting the modeling exercise creates a record that will be invaluable if guidance is later at issue in the context of a regulatory proceeding or lawsuit.

Ensure That Guidance is a Team Effort

Investor Relations, Finance, Legal, and the Disclosure Committee are just a few groups that should be involved in evaluating guidance before it’s issued. This evaluation should include a review of underlying assumptions, cautionary language, and anticipated Q&A topics. Preferably, Legal is vetting scripts to help avoid disclosure of items that can cause problems, including where analysts might press for details that the company isn’t planning on disclosing.

Ensure That Guidance is a Team Effort

Investor Relations, Finance, Legal, and the Disclosure Committee are just a few groups that should be involved in evaluating guidance before it’s issued. This evaluation should include a review of underlying assumptions, cautionary language, and anticipated Q&A topics. Preferably, Legal is vetting scripts to help avoid disclosure of items that can cause problems, including where analysts might press for details that the company isn’t planning on disclosing.

No Shame in Updating or Withdrawing Guidance

Once a material underlying factor changes—whether it’s correspondence from the FDA, an unexpected increase in tariffs, or pullback in customer demand—stale guidance can quickly cross into misleading territory. Speed matters in both market credibility and legal defense. This is especially true when management plans to speak with investors at conferences in between quarterly results announcements. And remember, while you might be sued for many things, it’s a rare day that withdrawing guidance, on its own, would be the main reason for a suit.

Parting Thoughts

The pressure to provide guidance is real. That said, regulatory and litigation risk have made issuing guidance much more than a routine investor relations exercise—it’s a strategic governance decision. Maintaining messaging discipline, calibrating assumptions, knowing when to say less, and anchoring communication in governance best practices are what separate companies that weather volatility from those that end up in the crosshairs of regulators and plaintiffs’ firms.

[View source.]