As digital health companies blossom from ideas into reality, navigating state regulations on the corporate practice of medicine (CPOM) is typically one of the first and most crucial legal hurdles to clear if the digital health company seeks to deliver professional healthcare services. Many states have strict rules about 1) what type of entities can perform medical services and 2) who can have an ownership interest in entities that provide those medical services. In many states, only a professional medical entity, and not a general corporation, can provide medical services. In addition, many states also limit ownership of professional medical entities to people with certain medical licenses. These ownership rules vary by state, though all states permit a licensed physician to be the sole owner of a medical group. For nonmedical personnel, including founders, venture capital firms, private equity, and other investors, this means that they generally cannot invest in entities that provide medical services.

Working with experienced healthcare legal counsel is essential, as misunderstanding these regulations can lead to invalid corporate structures, regulatory penalties, and allegations of unlicensed practice of medicine. Further, compliance with CPOM laws is essential for investments and successful exits as sophisticated investors view CPOM compliance as a fundamental risk factor in their investment decisions. Healthcare counsel will design compliant corporate structures—often involving management service organizations (MSOs) alongside professional corporations (PCs)—that protect both clinical independence and allow for appropriate financial relationships between investors and the medical practice while satisfying regulatory requirements across different jurisdictions. These regulatory frameworks can be exceedingly complex, with subtleties that vary significantly from state to state, creating an intricate legal landscape where even well-intentioned founders and investors can easily make critical mistakes that threaten the viability of their business model or expose them to substantial liability.

In this advisory, we discuss key considerations for digital health companies and their investors as they navigate state prohibitions on CPOM and provide helpful tips for ensuring that their corporate structure and business models are compliant with relevant laws and market expectations.

Who: CPOM Isn’t Just for Doctors

While state prohibitions on corporations practicing medicine are the most common, several states impose similar restrictions on other licensed professions, such as dentistry, nursing, counseling, psychology, veterinary medicine, and physical therapy. These restrictions fundamentally limit who can own and control entities providing these professional services—typically requiring that owners hold the appropriate license.

For entrepreneurs, investors, and nonlicensed business professionals looking to enter the digital health space, these regulations create significant barriers to traditional business ownership and investment structures. The core purpose of these laws is to prevent business interests from interfering with professional judgment and the provider-patient relationship.

These restrictions vary considerably from state to state in both scope and enforcement, making multi-state operations particularly challenging.

Why: Preserving the Sanctity of the Patient-Provider Relationship

The underlying public policy for state prohibitions on CPOM is derived from protecting the integrity of medical decision-making. CPOM laws aim to ensure healthcare professionals remain free from external influence (like a for-profit corporation's obligation to maximize shareholder value).1 State prohibitions on CPOM are similar to, and often intersect with, other laws aimed at preserving the sanctity of the patient-provider relationship, such as the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, the Stark Law, and fee-splitting rules. Furthermore, CPOM prohibitions address the risk that nonlicensed individuals such as founders and investors might effectively engage in medical decision-making, which could constitute the unauthorized practice of medicine—a criminal offense in most jurisdictions.

What: The MSO-PC Model

The most common and pressure-tested way for digital health companies and their investors to comply with varying state prohibitions on CPOM and avoid possible criminal and civil penalties is to establish two distinct corporate entities: an MSO and a PC. The MSO typically employs administrative staff and provides management, financial, coding/billing, marketing,2 and other administrative services to the PC, and may also serve as a lender to the PC. The PC employs the physicians and clinical personnel, owns all clinical assets (e.g., medical records), and is the entity through which all medical services are provided. Importantly, the PC’s physician owners control all decisions that involve medical decision-making.

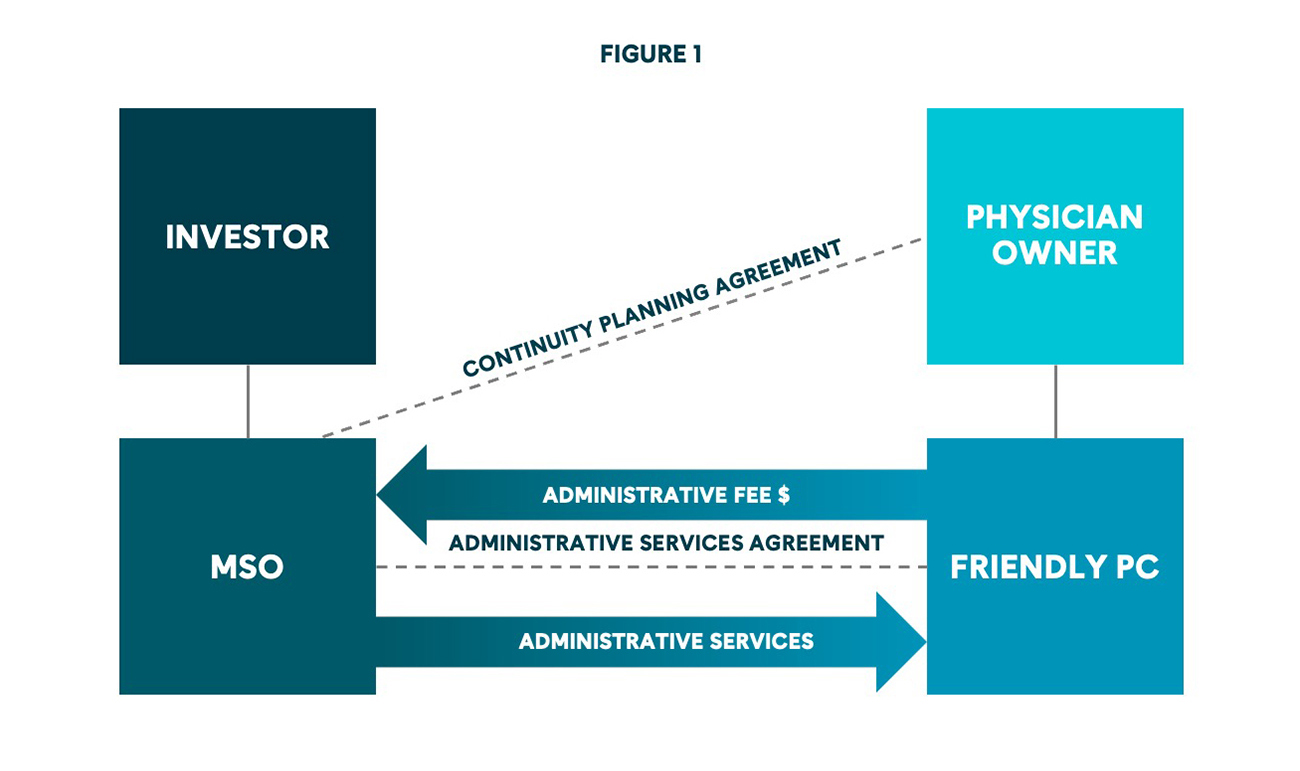

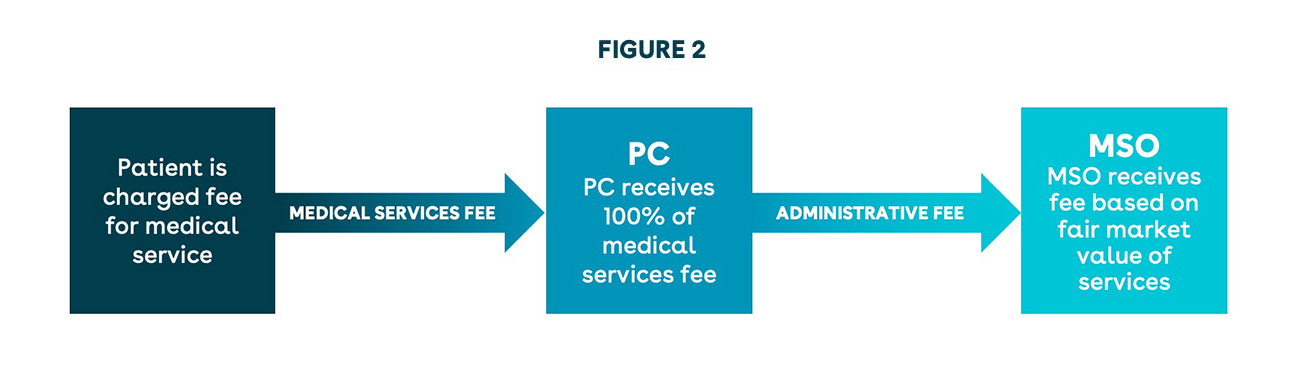

Because the MSO does not perform medical services, it can be owned by lay investors, including investment firms and other nonprofessional entities. In contrast, in states with prohibitions on CPOM, the PC must be owned by one or more actively licensed medical professionals. Below, Figures 1 and 2 provide simple visual representations of the relationships and flow of funds between these various parties. The use of the MSO-PC model allows investors to share in the profits of the management company while still complying with state laws that protect the integrity of medical decisions, which are made solely by the PC through its physician owner(s).

Figure 1 shows the MSO-PC model in its most basic form, but this model can grow and evolve depending on the wants and needs of a digital health company. For example, digital health companies eyeing national expansion will need to set up several PCs, as some states require that professional services be conducted only through domestic entities (corporations or professional entities that are formally registered and incorporated within that specific state), and then foreign qualify those domestic entities nationwide. Similarly, digital health companies working with multiple PC owners will need to navigate state licensing and professional corporation ownership requirements to understand whether one or more owners must be licensed in a given state in order for a professional corporation to do business there, even if they are not actually providing medical services in the state.

Figure 2 shows the flow of funds in a basic MSO-PC model. Typically, funds will first flow from a patient or payor to the PC in order to comply with state fee-splitting laws, which generally prohibit healthcare professionals from sharing clinical fees with nonlicensed entities or individuals. From these revenues, the PC first compensates its healthcare providers and then pays the MSO the administrative fee. Importantly, the administrative fee should reflect the fair market value of the services provided to the PC by the MSO, and ideally, the fair market value will be determined by a valuation expert. Ensuring fair market value is critical to demonstrating that the arrangement is a legitimate arm’s-length service relationship rather than disguised fee-splitting or an illegal kickback scheme prohibited by the anti-kickback statute.3 Depending on the needs of the digital health company, this flow of funds can be altered, but alterations can come with regulatory risk and should be carefully made with the advice of experienced healthcare regulatory counsel.

How: The Key MSO-PC Agreements

Setting up an MSO-PC model can require significant time, effort, and expertise and includes a variety of agreements between the various entities involved. Of those agreements, two are particularly important: the Administrative Services Agreement and the Continuity Planning Agreement.

Administrative Services Agreement

Importantly, the PC and the MSO are not part of the same corporate structure; they are not subsidiaries or affiliates. Instead, they are business partners, tied together contractually by an Administrative Services Agreement (an ASA, alternatively called a Management Services Agreement or MSA) which sets forth the relationship and obligations of both entities. Under a typical ASA, the MSO will provide management, financial, coding/billing, possibly marketing, and other administrative services to the PC, and may also serve as a lender to the PC. In exchange, the PC will pay an administrative fee to the MSO. The most common administrative fee structures are as follows:

- Fixed fee

- The safest way to structure the administrative fee between the MSO and the PC is to use a fair market value fixed fee for the services provided, which mitigates the risk that a regulator could interpret the fee as an unlawful kickback or referral scheme under state and federal anti-kickback statutes. This administrative fee is based on the fair market value of the administrative services provided by the MSO to the PC. To mitigate compliance risks, the fair market value should be determined by an independent valuation expert who can provide documentation supporting the reasonableness of the fee arrangement.

- This fee can be difficult to implement for growing practices where accurate budgeting/forecasting is difficult. This fee can be modified to include a variable component, but only with careful guidance from regulatory counsel.

- Cost-plus

- This fee is equal to the MSO’s actual cost of providing administrative services to the PC plus a fair market value markup, as determined by an independent valuation expert.

- Percentage-based

- This fee is based on a percentage of money that the PC brings in, and can be based on gross revenue, collections, etc.

- This fee can help to align the financial incentives of the MSO with those of the PC and can be relatively simple to calculate. However, this fee structure is the riskiest and some states explicitly prohibit this type of administrative fee.

Continuity Planning Agreement

The Continuity Planning Agreement (the CPA, alternatively called a Share Restriction Agreement or Stock Transfer Restriction Agreement) runs among the MSO, the PC, and the physician owner, and functions as the MSO’s (and the MSO’s investors’) “insurance policy” against a rogue or problematic physician owner. In essence, the CPA specifies the circumstances under which the physician owner can transfer their shares in the PC to another person/entity and requires the MSO’s consent for such a transfer. The CPA also sets forth certain circumstances under which the MSO can direct, or under which the physician owner is obligated to, transfer the physician owner’s shares (e.g., the physician owner’s medical license is revoked). The CPA may also set forth any indemnification obligations between the parties and other miscellaneous terms, such as dispute resolution and the terms governing any spousal consent. It is important to note that CPAs are not legal or enforceable in every state as some states believe they grant excessive control over the PC, and even in states where they are allowed, they must be carefully drafted to prohibit any such control. Accordingly, working with legal counsel to ensure the transfer of shares can be predicted is vital for investors.

Beyond these two key agreements, the MSO-PC model typically requires numerous additional documents, including professional services agreements, employment agreements, HIPAA business associate agreements, trademark licensing agreements, promissory notes, and more.

Other Important Considerations

All physician-related documentation—including agreements, job descriptions, and employee manuals—should emphasize that the physician will exercise their own independent professional judgment at all times and should prohibit any lay person or entity from interfering with such judgment. Beyond merely incorporating these independence provisions into written policies, companies must implement robust procedures that actively safeguard physician autonomy in day-to-day operations.

Further, maintaining CPOM compliance requires ongoing vigilance rather than a one-time effort. To maintain compliance with CPOM, digital health companies and their investors should conduct annual operational audits and training programs for all personnel involved in the MSO-PC relationship.

Digital health companies and their investors should be mindful of the risks and implications of violations of state prohibitions on CPOM. Violations can result in severe penalties, including criminal charges, jail time, substantial fines, loss of licensure, litigation, loss of reimbursement and payor agreements, and nullification of other business contracts, making compliance essential not just for legal operations but for protecting company valuation and long-term viability.

Conclusion

State prohibitions on CPOM can present a dizzying array of contrasting rules and obligations for digital health companies, but a properly structured MSO-PC model can help alleviate many of these concerns. Even then, digital health companies must pay attention to changing state and federal rules and enforcement priorities. For example, both California and Oregon state legislative bodies have introduced legislation seeking to curtail the use of the MSO-PC model in those states. Similarly, states such as New York and California and enforcement authorities such as the U.S. Department of Justice are increasingly scrutinizing digital health companies for compliance with state and federal law. For digital health companies at all stages of growth, we recommend working with experienced healthcare regulatory counsel to understand the state prohibitions on CPOM and intersecting and evolving state and federal requirements.

[1] Several states provide specific statutory exemptions to CPOM restrictions, most notably for hospitals that employ physicians. These exceptions typically exist where other regulatory frameworks provide alternative safeguards for clinical independence. However, these exemptions vary significantly by state.

[2] When marketing services are provided by the MSO to the PC, state and federal anti-kickback statutes may be implicated. This risk must be carefully mitigated as the consequences of violating anti-kickback laws are severe and can include criminal penalties and jail time.

[3]Under the federal Anti-Kickback Statute, offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving anything of value to induce referrals for services covered by federal healthcare programs is a felony, punishable by up to 10 years in prison and significant financial penalties.